Summary

On 9 May 2018, the body of Blessing Matthew, originally from Nigeria, was discovered in the Durance River, in the French Hautes-Alpes near the border with Italy. The Gap court opened an investigation but eventually dismissed the case on 9 February 2021 without shedding any light on the circumstances of her death or determining any responsibility for it. Border Forensics has produced this counter-investigation to support Blessing’s family and the NGO Tous Migrants in their quest for truth and justice. We have produced a spatio-temporal analysis of the events that took place on 7 May 2018 in the village of La Vachette, where Blessing was last seen alive. We analysed the contradictory statements of the gendarmes who attempted to stop Blessing in this village, and collected the in situ testimony of Hervé S., Blessing’s fellow traveller who witnessed the events leading to Blessing’s fall into the Durance. By cross-referencing multiple elements of evidence, our counter-investigation challenges the findings of the judicial police investigation that cleared the gendarmes of all responsibility. On the contrary, the new elements we present here suggest that by chasing Blessing, the gendarmes may have put her in danger, leading to her fall into the Durance and ultimately to her death. Our analysis thus supports the request to reopen the investigation; that alone can provide definitive confirmation of the events that led to Blessing’s death and determine the responsibility of those involved.

Introduction

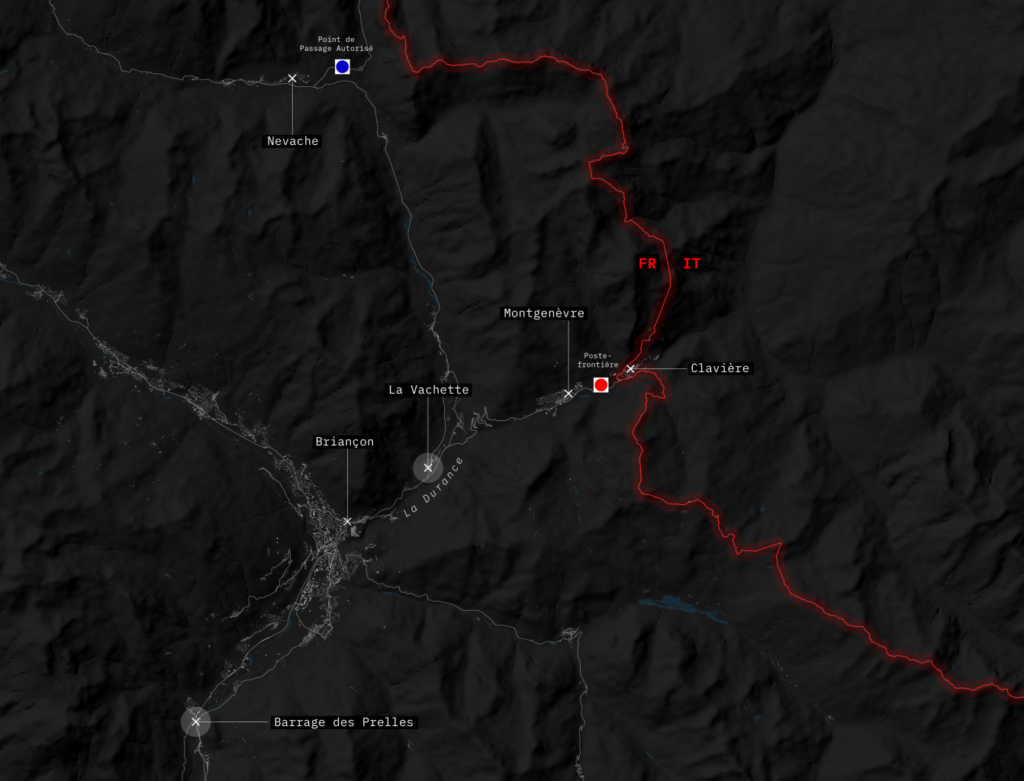

On 9 May 2018, the body of a young black woman was discovered in the Durance River, stuck in the dam of Prelles, a small village in the municipality of Saint-Martin-de-Queyrières, downstream from Briançon in the French Hautes-Alpes.

The young woman was identified a few days later as Blessing Matthew, aged 21 and originally from Nigeria. She was last seen alive on 7 May in the village of La Vachette, 15 kilometres from the French-Italian border, when the mobile gendarmerietried to stop her and her two fellow travellers, Hervé S. and Roland E.1The Gendarmerie is a branch of the French Armed Forces placed under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of the Interior, with additional duties from the Ministry of Armed Forces.

Beyond the grief of her family and her two fellow travellers, Blessing’s death led to a public outcry, as it materialised civil society’s fears that the militarisation of the Alpine border might endanger the lives of transiting migrants. Blessing Matthew’s death was the first documented case of a migrant dying in the region of Briançon since border controls were reintroduced at the border with Italy in 2015. Two more people have died in the region since.

On 14 May 2018, Tous Migrants, an NGO based in the region defending migrants’ rights, sent a report concerning Blessing’s death to the Gap public prosecutor, outlining the facts reported by one of the two fellow travellers who accompanied Blessing on the day of her death. This report was followed by a legal complaint filed on 25 September 2018 by one of Blessing’s sisters, Christiana Obie, to the Gap public prosecutor for “endangering the life of others” and “manslaughter”.

On 10 December 2018, the police officer in charge of the investigation sent the summary of findings of the investigation to the Gap court, which concluded that the constituent elements of the alleged offences had not been demonstrated.

On 3 May 2019, Blessing’s sister and Tous Migrants filed a new civil suit. On 18 June 2020, the Gap court declared the complaint inadmissible and dismissed the case ab initio. The order of the investigating judge was confirmed by the investigating chamber of the Grenoble Court of Appeal on 9 February 2021.

To date, the judicial process has failed to shed light on the circumstances that led to Blessing’s death, or to determine who was responsible for it. However, Blessing’s family has not given up its quest for truth and justice. In the words of Christiana Obie, “my sister will continue to scream” until the truth is known and justice is done.

It is to support the demand for truth and justice of Blessing’s family’s that Border Forensics has conducted a counter-investigation, in collaboration with Tous Migrants and thanks to the crucial testimony of one of her fellow travellers, Hervé. But the stakes of our investigation go well beyond this specific case. The death of Blessing is only one of 46 deaths recorded at the French-Italian border since 2015. No responsibility has been established so far for any of these deaths. The practice of endangering migrants’ lives at the border has thus been allowed to continue unchallenged. We hope that this investigation will contribute to ending this impunity, and put an end to these practices.

Methodology and outline

Through a reconstruction of the events in space and time, based on the confrontation of multiple sources of data and evidence, we have reconstructed as precisely as possible the events leading up to Blessing’s fall into the Durance, which had been blurred by the omissions and contradictions of the judicial police investigation.

Our analysis was carried out in several stages and by combining different methods, each of which revealed new elements concerning Blessing’s death.

First, we analysed the political and legislative context and the border control practices in the Alps which shaped the conditions of Blessing’s death. To begin, we synthesised the academic literature and reports of associations. In addition, Sarah Bachellerie and Cristina Del Biaggio created a database of cases of migrants who died while trying to cross the borders cutting across the Alpine territory and analysed a database of pathologies documented among migrants in the Briançon region.

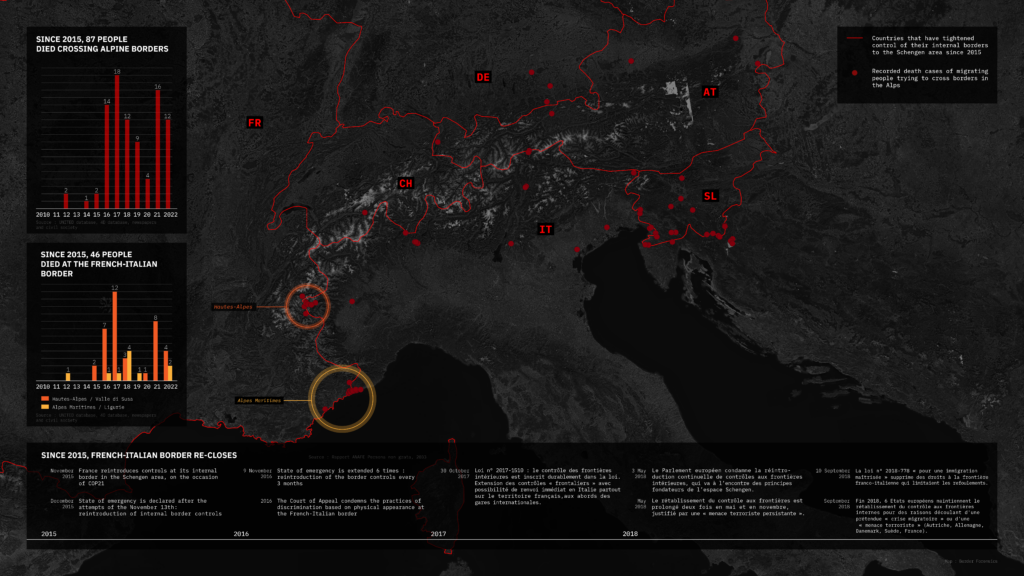

Our research shows that 87 people have died crossing Alpine borders since 2015, when the Alpine states closed their Schengen internal borders. We also note that the French-Italian border is the deadliest within the Alpine space, with 46 deaths identified. Furthermore, we show that the danger migrants are subjected to is also measured in a large number of pathologies identified in connection with border crossings. Finally, our research shows that in the area of Briançon, police practices that violate the rights of migrants and endanger their lives (chases, physical and verbal violence at the border crossing point in Montgenèvre) were particularly recurrent in the months and weeks preceding and following Blessing’s death. Our analysis of practices of control and their effects indicates that Blessing’s death is not an isolated event, but the result of a conjuncture of political decisions and police practices that endanger migrants from the “Global South” in their crossing of the Alpine borders.

Second, on the basis of the precise elements noted by Tous Migrants in the judicial police investigation file, which they then passed on to us as notes, we analysed the statements of the mobile gendarmes who were patrolling La Vachette on the night of Blessing’s death. These gendarmes were, along with Blessing’s two fellow travellers, the last people to see her alive. We verified the plausibility of the elements described in their statements in space and time, by reconstructing them in the village of La Vachette and then mapping them, which enabled us to detect numerous contradictions.

While the judicial police investigation constructed a homogeneous narrative from the gendarmes‘ contradictory statements and concluded that they had done everything possible to “keep [Blessing and her companions] out of the danger zone”, we demonstrate that the gendarmes‘ statements contradict each other, and that the events they describe are inconsistent with the constraints of space and time. Moreover, contrary to what the results of the judicial police investigation claim, the gendarmes‘ accounts do not enable us to exclude the possibility that they endangered Blessing.

Third, we went to La Vachette with Hervé S., one of Blessing’s fellow travellers who was at her side during what he describes as a chase, until Blessing fell into the river. This direct witness was not interviewed in the judicial police investigation. His testimony is accurate and consistent, and is corroborated by several other testimonies as well as material evidence. It sheds a fundamentally new light on the events leading up to Blessing’s death, and contradicts both the statements of the gendarmes and the findings of the judicial police investigation. It describes the circumstances and location of her fall for the first time.

Hervé declares that he saw the gendarmes chasing Blessing through a garden on the right bank of the Durance, until she reached the impassable boundary of the river. Then he saw a gendarme grab her arm and, as she tried to free herself from his grip, she fell into the water. After she fell, according to Hervé, the gendarmes stayed in the garden without helping her.

We conclude with a synthesis of the new elements brought by our counter-investigation to the understanding of the circumstances of Blessing’s death:

- Our analysis shows that the gendarmes’ statements are contradictory and inconsistent. Contrary to what the judicial police investigation claims, the statements of the gendarmes on which the investigation is based do not allow us to conclude that there was no chase and no endangerment of Blessing by the law enforcement officials.

- We demonstrate that Hervé S.’s account of the events, describing the chase, the place and location of Blessing’s fall and the involvement of the gendarmes is corroborated by several testimonies and material evidence. Our analysis of the recurrent and documented police practices of endangerment at the border in the Briançon area lends further credibility to the description of the events given by Hervé and casts doubt on the gendarmes’ statements.

Our analysis discredits the findings of the judicial police investigation that led to the closure of the judicial proceedings. The new evidence we present indicates that by chasing Blessing, the gendarmesmay have put her in danger, leading to her fall into the Durance and her death.

This analysis supports the request to reopen the investigation, a step which is essential to definitively establish the sequence of events that led to Blessing’s death and to determine those responsible it.

So as not to reduce Blessing’s life to the circumstances of her death, we have further sought to give an account of who Blessing Matthew was. To do this, we went to meet her family. Our counter-investigation for Blessing is a response to her family’s demand for truth and justice, and a tribute to her.

Her name was Blessing Matthew

While Blessing’s death and the circumstances that led to her fall into the Durance River moved the community of Briançon and beyond, only fragments of her life were made public: her age, her country of origin, and a photo of her posing on the day she graduated from high school.

To understand who Blessing was, and how she ended up crossing the Alpine border on the night of 7 May 2018, we met Christiana Obie and Happy Matthew, Blessing’s two sisters living in Italy, in February 2022.

Through them, we were able to get a glimpse into Blessing’s life and dreams. Blessing was the youngest of nine children. She grew up in a village in the Edo State area, and was raised by her mother, who worked on a farm. She was close to her two sisters, Christiana, the older, who always had a special affection for her, and Happy, who was closer to her in age. Happy and Blessing enjoyed wearing the same clothes, so that everyone called them “the twins”. Her sisters tell us that Blessing had a joyful nature, full of imagination and ideas to share with others. She loved to tell her brothers and sisters the news of the neighborhood, which earned her the nickname “BBC News” in her family. Always ready to care for others, she dreamed of becoming a doctor and building an orphanage. Blessing loved to sing and dance to put the house in a good mood. The song “Eyes don clear” by the Nigerian band Jungboys was one of her favourites.

Beyond deaths, the border’s impact on the health of those who cross itChristiana and Happy also helped us to reconstruct Blessing’s journey from Nigeria to Italy, where her older sister, Christiana, was already living. Leaving Nigeria together in early 2016, Blessing and Happy were stranded in Libya for a few months, then crossed the Mediterranean in the fall of 2016 on two separate boats. While Blessing’s boat arrived in Italy, Happy’s was stopped by the coast guard. After being turned back to Libya, Happy was then sent back to Nigeria, from where she restarted her journey to Italy via Libya and the Mediterranean. During her stay in Italy, which lasted until early May 2018, Blessing was housed in a reception center for asylum seekers in Turin. Over this time, she was not able to secure the right to stay, or to find work. On the evening of May 6, Blessing called, for the last time, her sister Happy, who had recently landed in Italy. She informed her that she planned to cross the border to go to France on foot.

The Alps’ lethal borders

When Blessing decided to reach France from Italy in May 2018, in front of her lay the Alps, a mountain range that has been constructed as a border.

The Alps lie within the Schengen area, a territory where free movement is a founding principle. However, as Sara Casella-Colombeau points out, the area of free movement established on the European territory “has not prevented maintaining control mechanisms at internal national borders”.2cairn.info/revue-plein-droit-2010-4-page-12.htm

In the context of significant migratory movements in 2015, European states, in particular those bordering Italy (Austria, Switzerland and France), reintroduced systematic controls at their borders. Thus, since 2016, there has been a gradual closure of “Alpine crossings” for people from the “Global South” who, like Blessing from Nigeria, do not have access to visas to enter and stay in European Union (EU) states.

Following these political developments along the external and internal borders of the EU, more and more violations of migrants’ fundamental rights are reported. Faced with the risk of being turned back, migrants are forced to bypass designated border checkpoints and take other, more dangerous routes.

Our research shows that this closure has led to an increase in the number of accidents and deaths of people when they try to cross Alpine borders: 87 people have lost their lives in this way since 2015. The highest number of deaths is recorded at the French-Italian borders, with 46 deaths recorded since 2015.

This significant figure is explained by the combination of an increased number of crossings of this border along with particularly restrictive policies instituted by France. Indeed, on 22 October 2015 France “temporarily” reintroduced controls at its borders, in addition to mobile controls in the 20-kilometer border zone provided for in the Schengen Borders Code. This mechanism was renewed with the proclamation of the state of emergency following the November 2015 terrorist attacks, and is still in force today3On 10 May 2022, the Ligue des Droits de l’Homme, Anafé, Cimade and Gisti filed an appeal for annulment, along with a summary suspension, against the Prime Minister’s decision to extend the temporary reintroduction of controls at all internal borders of the Schengen zone from 1 May 2022 to 31 October 2022. URL: https://www.ldh-france.org/la-ldh-lanafe-la-cimade-et-le-gisti-contestent-la-prolongation-injustifiee-du-controle-aux-frontieres-interieures-mise-en-oeuvre-par-le-gouvernement-francaise/. On 30 October 2017 a new law added a 10-kilometer zone around designated border crossing points and international ports of arrival where police can conduct identity checks.4https://www.editions-legislatives.fr/actualite/la-loi-renforcant-la-lutte-contre-le-terrorisme-etend-a-nouveau-les-controles-d-identites-frontalier

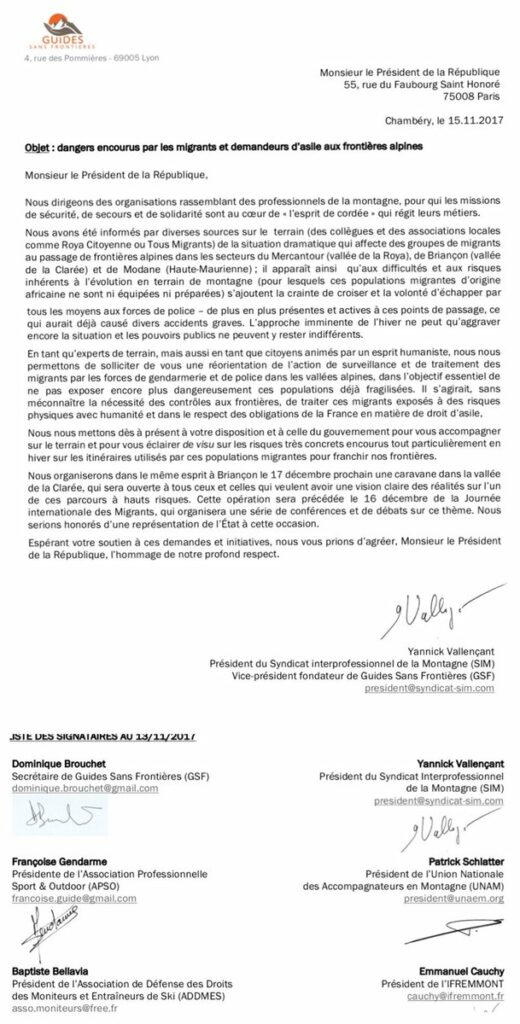

“No deaths yet, but that will come, Mr. President”

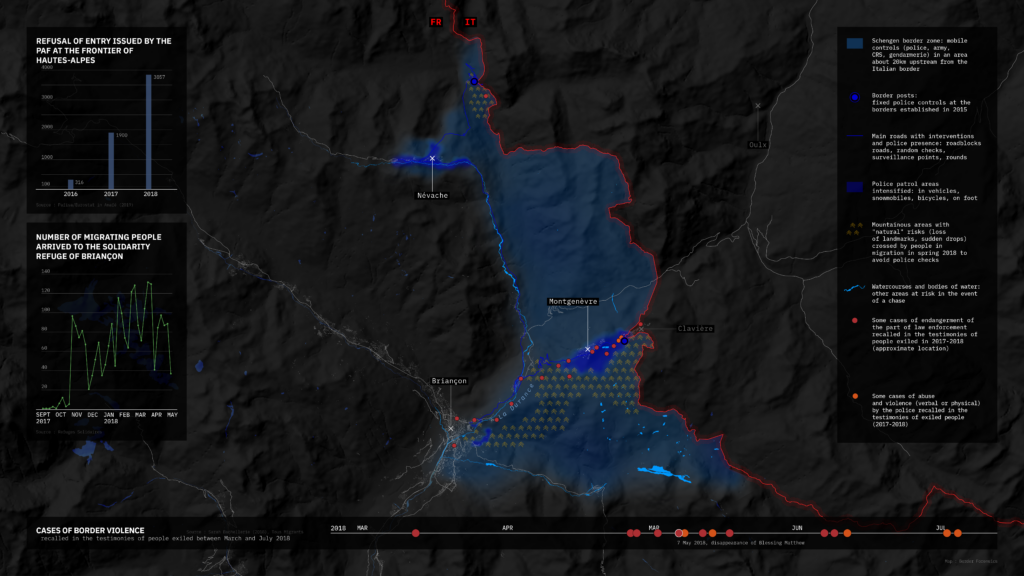

Starting in 2017, more and more migrants have been trying to cross the border through the Hautes-Alpes, from the Susa Valley. Since June 2017, the Ministry of the Interior has sent reinforcements of mobile gendarmes and the army to support the border police to strengthen migration controls. This has not discouraged people seeking refuge from trying to reach France through this passage, as demonstrated by the graph of data on arrivals at the Refuge Solidaire in Briançon (see the data visualised below).

During this period, associations advocating for foreigners’ rights that are present in the region have not only noted an increase in the number of people sent back to Italy, but also an increase in police practices that endanger migrants5The observation report Persona non grata published by Anafé in 2019 concludes that at the French-Italian border, “exiled persons are subjected daily to illegal practices of the French administration, which does not respect the legislation in force, implements expeditious procedures and violates human rights and international conventions yet ratified by France.” URL: http://www.anafe.org/spip.php?article520. For example, on 19 August 2017, two young men fell 40 meters into a ravine while fleeing from the sight of the gendarmes, hiding in a tunnel. One of them remains injured for life. The border crossing also marks bodies in a non-lethal way, as shown by the analysis of data collected by medical units in the Briançon region (see box).

In December 2017, the Citizen Collective of Névache addressed an open letter to the President of the French Republic, Emmanuel Macron, in which it warned about the risk of death faced by migrants in the Briançon region:

“During the month of December, we have had to call Mountain Rescue on at least six occasions to […] avoid the death [of migrants], not without avoiding frostbite and various injuries. No deaths have been recognized yet, but that will come, Mr. President.”6https://www.laprovence.com/article/societe/4774520/briancon-le-collectif-citoyen-de-nevache-adresse-une-lettre-ouverte-au-chef-de-letat.html

Blessing’s death, only a few months later, thus vindicated the warnings in the letter to President Macron.

Beyond deaths, the border’s impact on the health of those who cross it

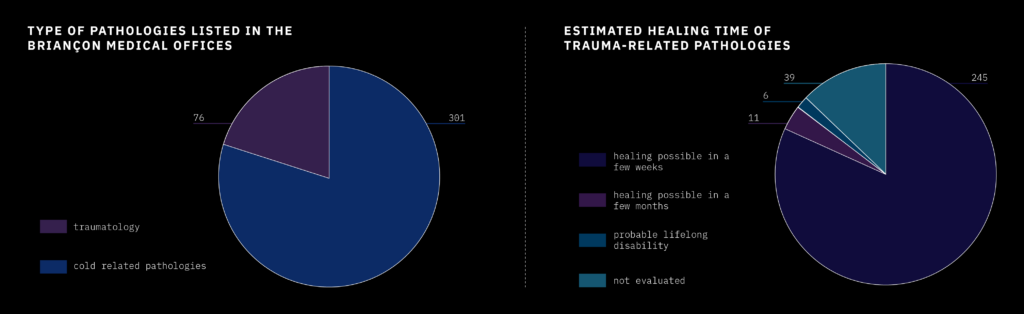

Using statistical data concerning pathologies observed among migrants having crossed the border collected as part of a medical dissertation defended by Chloé Lecarpentier in 2019,7 we we analysed the effects of crossing the border on the health of those who cross.

The data cover a 19-month period from May 2017 to November 2018. Of the 1,637 people who were examined by a doctor at the Briançon hospital or at the Refuge Solidaire medical unit after crossing the border, 385 indicated pathologies (23.5%) that can be attributed to the border crossing itself (cold-related pathologies and localised injuries).

Using the same data, we also tried to assess the severity of injuries and muscle pain by evaluating the probable recovery time. The results show that, out of 301 cases, for 245 of them recovery in a few weeks seemed probable. In 11 cases, the recovery time was estimated to be a few months, and in 6 cases, lifelong consequences were expected. For 39 cases, i.e. 13%, it was not possible to make any assumptions about the recovery time.

Spring 2018, increased militarization and escalating violence

Blessing attempts the Alpine crossing in the spring of 2018, amidst heightened tensions and an increase in practices that put people’s lives in danger.

Between March and June 2018, 14 cases of law enforcement officers chasing migrants were documented in the Briançon border zone. In addition, there are other types of dangerous practices, such as hiding and suddenly appearing to take migrants by surprise (which the people stopped experienced as ambushes or traps). These practices increase the number of falls resulting in injuries. In addition to rights violations, there is an increase in verbal and physical violence against migrants inside the border post. Thus, as Sarah Bachellerie’s research7Sarah Bachellerie, 2019, « Traquer et faire disparaître. La fabrique de l’invisibilité du contrôle migratoire à la frontière franco-italienne du Briançonnais », MA Thesis. shows, the combination of racial profiling and situations of endangerment during arrest means that police control of the border zone often operates as the tracking of racialized migrants across the mountain range8https://journals.openedition.org/rga/7248.

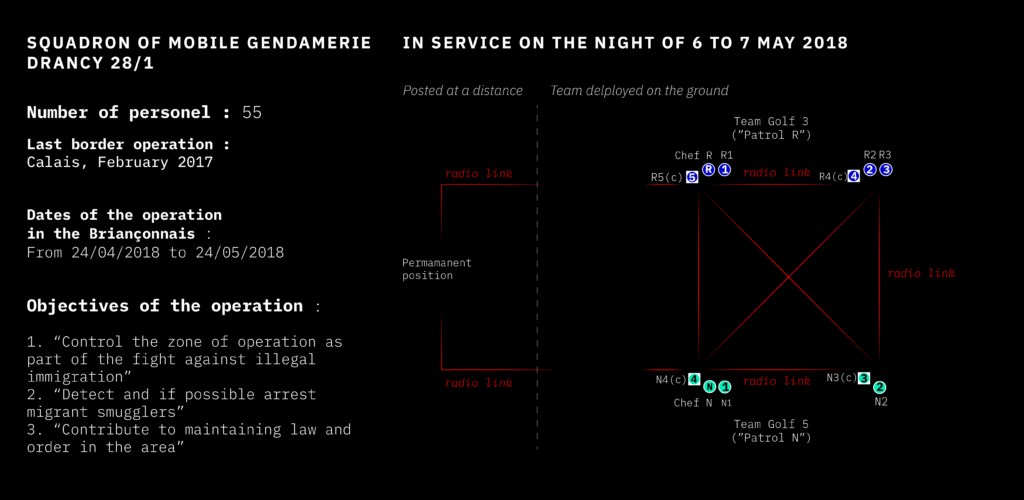

On 24 April 2018, when the situation in the Hautes-Alpes was made even more tense by the actions of the far-right group “Génération Identitaire”9https://www.mediapart.fr/journal/france/220418/dans-les-hautes-alpes-le-coup-de-com-des-identitaires-contre-les-migrants , the Ministry of the Interior deployed reinforcements of CRS10The “Compagnies républicaines de sécurité” abbreviated CRS, are the general reserve of the French National Police. and a mobile gendarmerie squadron, Squadron 28/1 from Drancy, in the region. The latter had a triple mission: “fight against irregular and illegal immigration”, “detect and arrest migrant smugglers” and “contribute to upholding order”. The gendarmes have a formal directive: “not to put people in unnecessary danger”, which implies “not to start a chase” and “not to corner” fleeing people in risky areas. They are forbidden to “take ski slopes, snow-covered slopes, cross rivers or streams”.

The deployment period of the Drancy squadron in the Hautes-Alpes corresponds to an increase in testimonies from migrants attesting to rights violations as well as endangerment by law enforcement officials – mobile gendarmes and border police. The chronological distribution of these testimonies indicates that cases of violence increased in the weeks before and after Blessing’s death.

On the night of 6 to 7 May 2018, two patrols from the Drancy squadron, led by Chiefs R and N, were stationed in the area between Montgenèvre and the Col de l’Échelle when their members confronted Blessing and her fellow travellers near La Vachette.

Reconstruction of the events of 7 May 2018

From Clavière to La Vachette, the destinies of Blessing, Hervé and Roland cross paths

It is in this context of heightened tension that Blessing, Hervé and Roland, who arrived independently of each other, met on the evening of 6 May 2018 at the self-organised refuge in Clavière, in close proximity to the border. The refuge was opened in March 2018 in the basement of the village church by activists and migrants to provide accommodation at a time when the border police were turning people back to Clavière, often in the night and the cold, leaving them without assistance.

The paths of Herve A. and Roland E.

On the night of 6 May, Blessing arrives in Clavière and meets Hervé S. and Roland E.

Hervé left Cameroon in 2016 with his wife and son to escape threats against him. They travelled to Algeria and then, faced with difficult living conditions, the family decided to travel to Europe via Libya. While crossing the Mediterranean, their boat sank and his wife and child lost their lives. The only survivor of the family, Hervé disembarked in Catania, Italy on 8 January 2018, traumatised. He did not receive the care he needed and left Catania for Turin, where he stayed for a while in a reception centre. Because he spoke French, he decided to go to France, the country which had been his destination all along. During their border crossing on the night of 6-7 May 2018, Hervé stayed close to Blessing, supporting her as she struggled to walk. He justifies his actions as follows: “I tried to do for Blessing what I couldn’t do for my wife and son.”

Roland’s account, collected by Tous Migrants, is less complete, but tells that he left Nigeria. He arrived in Sicily in February 2017 via Libya. After staying for a while in Calabria and Naples, he headed to Turin in order to cross the French-Italian border.

Hervé remembers the impression Blessing made when they met: a “happy girl” despite her growing stress as the time of departure approached. However, like the rest of the group, Blessing kept her spirits high, not thinking “of the worst” but of the joy of meeting the others in France.

According to the testimonies of Hervé and Roland, they left Clavière in a group of twenty-five people shortly before midnight.

The group set off into the forest towards Briançon, past the border post and further up the mountain. Blessing walked more slowly and the group decided to split up, with only Hervé and Roland remaining with her. Blessing and her fellow travellers then continued on their way, walking on the main road so as not to get lost.

According to the judicial police investigation, which the association Tous Migrants had access to, at 3:50 am Roland’s phone pinged a cell tower located less than 2 kilometres from La Vachette.

Around 4am, Blessing, Hervé and Roland arrived at the entrance of the village of La Vachette, where they could see the church, which they identified as a landmark near a refuge. It was at the entrance of the village that the mobile gendarmerie patrol from Drancy tried to stop them.

From that moment on, the accounts of the gendarmes and Hervé diverge completely. We analyse these contradictory accounts one after the other.

The gendarmes’ statements: a web of contradictions

As part of the judicial police investigation, investigators interviewed the 11 mobile gendarmes from Drancy Squadron 28/1 who were patrolling the border area on the night of Blessing’s death. Aside from Hervé and Roland, these gendarmes were probably the last people to see Blessing Matthew alive.

In the summary of findings, the police officer in charge of the investigation found that:

“All the findings and testimonies of the people directly involved converge to exclude the possibility that there was an ambush, a chase or breaches of the obligations of safety and caution.”

The investigators considered the gendarmes’ testimonies consistent, plausible and coherent. Based on the elements of this investigation, the Gap public prosecutor closed the case for lack of an offence.

However, in 2020, the association Tous Migrants analysed the gendarmes’ testimonies collected in the judicial police investigation file and noted numerous inaccuracies, inconsistencies and contradictions.

Based on the notes provided by Tous Migrants, Border Forensics went to La Vachette in October 2021 to test the gendarmes’ statements in space. We produced video documentation that enabled us to then produce a spatio-temporal analysis of the gendarmes’ accounts.

We focused our reconstruction on the statements of the six mobile gendarmes of the patrol led by Chief R. On the night of 6 to 7 May 2018, Patrol R was working in the sector between Montgenèvre and Briançon.

Despite the discrepancies between the testimonies, we identified 4 key stages that structure the gendarmes’ accounts. We analysed the contradictions that emerge during these stages one by one.

Stage 1

The “statement of facts” from the judicial police investigation indicates that the gendarmes saw the three “migrants” at around 6am, “near La Vachette”, “while it was still dark”. According to the investigators, “the gendarmes clearly identified themselves out loud, the migrants wanted to evade the control by fleeing in a scattered way towards the centre of the village of La Vachette, taking advantage of the still dark night at that time”. However, the gendarmes’ testimonies differ as to the time of this event: some place the scene at 5:20 am, when it was still dark, others at 6am, when it was already light.

The gendarmes’ statements also contradict each other as to the location where the three figures were seen and their own location at the time they saw them. Finally, some gendarmes state that they followed the people on foot, while others describe following them by car towards the centre of the village.

Thus, already at this first stage, we see that many contradictions have been concealed in the findings of the judicial police investigation, and that the possibility that there was a police chase is erased from the findings of the investigation.

Stage 2

In the centre of the village, the gendarmes found themselves in front of the paved bridge over the Durance. All of them, except for Chief R, stated that they had entered the village by car. However, the three passengers in the same car made three different statements.

Without taking these contradictions into account, the judicial police investigation establishes that the migrants “scattered running in the night”, on the right bank of the Durance. According to the investigators, thanks to the action of the gendarmes, the migrants crossed the bridge, going further towards the centre of the village and thus moving away from the dangerous river.

However, none of the gendarmes claimed that the three people had gone to the right bank. Furthermore, the trajectories they describe at this point are completely different.

Thus, the judicial police investigation, by placing the “migrants” and the gendarmes on the right bank, did not take into account the divergence of accounts. Moreover, contrary to the investigation’s conclusion ruling out the possibility that the gendarmes had endangered the fugitives, several gendarmes described the migrants approaching the river, precisely because they were being chased.

Stage 3

The findings of the judicial police investigation establish that, “at no time”, were the gendarmes in contact with the migrants in the village. However, several gendarmes indicate that they saw and verbally questioned an individual near the church.

Two gendarmes say that they carried out searches near the church with their colleagues , and then at the same place they verbally questioned an individual and found a rucksack.

On the other hand, neither of their colleagues spoke of having carried out a search near the church, nor of having seen an individual, nor of having found a rucksack at that location.

As for the two drivers, they stated that they had driven around in their cars, during which time they remained in radio contact with their colleagues, who had not reported seeing an individual, but had found a rucksack. Thus, in stage 3, once again, the findings of the judicial police investigation concealed the many contradictions in the gendarmes’ statements.

Stage 4

The last stage consisted of a period of searching for an unclear period of time, which some gendarmes said was on the left bank, until the arrival of reinforcements from Patrol N. According to the findings of the judicial police investigation, “the gendarmes carefully scanned the banks of the Durance”, but “did not detect any presence”.

However, two gendarmes said that they had seen silhouettes: according to one of them , it was a single figure, which he did not locate on one bank or another; according to the other , it was two figures on the left bank of the Durance, heading towards Briançon.

No other gendarme mentions these figures and the areas that were searched are not the same from one gendarme to another. Thus, the judicial police investigation, by situating the gendarmes on the immediate banks of the Durance, in search of the migrants with the intention of protecting them, once again erases the multiple temporal and spatial differences between the gendarmes’ testimonies.

Our analysis brings to light major contradictions between the gendarmes’ statements, which turn out to be impossible in time and space. We show that the judicial police investigation almost systematically erased these contradictions. We thus question the statements of the gendarmes on which the judicial police investigation is based, and thus the findings of the investigation, in particular concerning the absence of a chase and endangerment. The absence of a chase and endangerment is also questioned by the finding that these police practices are recurrent in the Briançon borderzone.

Hervé S.’s testimony: the chase and Blessing’s fall into the Durance

Hervé, one of Blessing’s fellow travellers, was never interviewed in the judicial police investigation. After being pushed back across the border to Italy, and feeling threatened, Hervé refused to answer the calls of the French investigators. While in the judicial police investigation, the investigators credit him with a few incomplete remarks from a telephone conversation, Hervé denies having had this conversation. His testimony in the context of our counter-investigation thus sheds new light on the events.

The sequence of events according to Hervé S.

Stage 1

About 4 am. Hervé, Roland and Blessing arrive at the entrance of the village of La Vachette via the RN94. Roland sees torches and they hide by the side of the road. After ten minutes, Roland gets up and continues to walk along the road. He is once again lit up by the torches and the gendarmes order him to stop. Blessing and Hervé come out of their hiding place and run in the direction of the church.

Stage 2

They arrive at the bridge in the centre of the village. Blessing drops her bag just before the bridge, Hervé bends over to pick it up. He sees four gendarmes coming towards him on foot, from two different directions, their torches on.

Stage 3

Being chased by the police, Blessing and Hervé cross the bridge and continue to run towards the church. Hervé goes down into a garden below the church, where he hides by lying in high grass. Blessing goes down the stairs into the same garden. A gendarme arrives running behind her saying “Stop, if you don’t stop I’ll shoot”.

Stage 4

About 4:20 am. Blessing continues to run in the garden, the gendarme runs after her. She stops when she finds herself blocked by the river. Cornered by the gendarme, she continues along the riverbank. She says to the gendarme, in English, that she will jump in the water if he continues to chase her. The gendarme reaches her, grabs her by the arm, she struggles. She screams in English: “Let me go, let me go, let me go.” Then Hervé no longer sees her. He hears her scream in English “Help me, help me, help me”, then he hears her voice growing distant.

Hervé sees the gendarme go up and join his colleagues in the garden. He hears the gendarme say “She fell, she must have crossed to the other side”. The gendarmes stay in the garden for longer than ten minutes, searching and looking for Hervé. Then, three gendarmerie vehicles stop in the parking lot, and the gendarmes join their colleagues.

5 am. The street lights come on. Hervé crawls to a hut to hide better. He sees torches on the other side, on the left bank. He stays hidden for about an hour.

The rest of Hervé’s testimony

6 am. The church bells ring. Hervé leaves his hiding place and tries to reach the church to ask for help. He is then seen by the gendarmes who call out to him. He runs and hides in the garden again, in the same place as before. The gendarmes don’t stop him. About half an hour later, he comes out of his hiding place again to find help. On the road near the church he is once again seen by the gendarmes.

These gendarmes chase him to the edge of a wooded area at the end of the village, in the direction of Val-des-Prés. There, the gendarmes catch him, beat him, and handcuff him.

Hervé is then brought back to the border post, where he can charge his phone. At 7:15 am, he manages to call Roland. Then Hervé is sent back to Clavière, on the Italian side.

We reconstructed Hervé’s testimony, which is an essential new element to make progress in the search for the truth for Blessing, by combining several methodologies.

First, in October 2021, we went to La Vachette with Hervé to document his testimony in situ. Returning to the scene is a ‘mnemonic device’, central to the method of forensic architecture, which helps people to “recall incidents obscured by the extremely brutal and traumatic nature of their experience”11Eyal Weizman, 2021, La vérité en ruines. Manifeste pour une architecture forensique, La Découverte, p.65.. Our method involved positioning members of our team and of Tous Migrants in space to stand in for the people Hervé mentioned in his testimony. We further positioned a video camera close to Hervé at key moments in the events. Through the camera we were was able to verify that it was possible to see everything he described. In the process, the video generated the missing images of the events of 7 May 2018.

Second, we created a photogrammetric (3D) model of the village of La Vachette to reconstruct the light conditions at the time of the events, which we re-verified with Hervé.

Third, we produced a cartographic analysis of Hervé’s testimony to better understand the sequence of events in space and time. In this analysis stage, we also confronted and corroborated Hervé’s account with other elements of evidence. Through this process, we spatially reconstructed the circumstances Hervé described as having led to Blessing’s death.

In contrast to the vague and contradictory statements of the gendarmes, Hervé’s account is precise and coherent. It is also corroborated by several elements: on the one hand, the testimonies of fellow traveller Roland E. and of Jérôme P., who was living near the church of La Vachette at the time of the events; on the other hand, by several material elements, such as the time of Roland’s call and the time at which the street lights came on. Moreover, the practices of being chased by the gendarmes as he describes were documented repeatedly at the border. Hervé’s account therefore appears to be credible in terms of our analysis, and the events he describes plausible.

Our spatio-temporal analysis of Hervé’s account fundamentally contradicts the results of the judicial police investigation. By describing, for the first time and with precision, the circumstances and location of Blessing’s fall and the involvement of the gendarmes in it, this testimony sheds new light on the events and constitutes crucial progress in the search for the truth for Blessing.

Neither the gendarmes’ account, nor that of Roland, nor that of Hervé, make it possible to know what happened to Blessing between the moment she fell into the Durance and the moment her body was found at the Prelles dam, 11 kilometres downstream. One element of the judicial police investigation makes this unclear part of the events even more disturbing: a black jacket and a coloured scarf were found by the investigating gendarmes under a footbridge upstream of the point where Blessing fell. This jacket and scarf correspond to the description Roland and Hervé gave of the clothes Blessing was wearing until the moment she fell into the water.

What happened to Blessing after her fall? How did her jacket and scarf end up upstream of the point where Hervé testifies that he saw her fall? How did Blessing’s body get to the Prelles dam, 11 kilometres away?

Only reopening the investigation can provide a definitive answer to these questions and shed light on this still unclear part of the events.

Conclusion

Our analysis has brought to light crucial new elements concerning the circumstances of Blessing’s death that call into question the findings of the judicial police investigation.

First, by analysing the gendarmes’ statements in space and time, we have demonstrated their contradictions and inconsistencies. Whereas the judicial police investigation considered that “all the findings and testimonies of the people directly involved converge to exclude the possibility that there was an ambush, a chase or breaches of the obligations of safety and caution”, we have shown that these statements do not prove the absence of a chase. Furthermore, the recurrent endangerment practices observed at the border reinforce the grounds to question the findings of the investigation.

Second, we have analysed a critical new element: the in situ testimony of Hervé S., one of Blessing’s fellow travellers. This testimony had not been collected as part of the investigation, which only credited Hervé with a incomplete statements made during a telephone conversation, which he denied having had, with the investigating gendarmes. We have shown that this new testimony, contrary to the statements of the gendarmes, is precise and consistent in space and time, which we were able to verify by reconstructing it in situ at La Vachette. It is also corroborated by other evidence, including the testimony of Roland E. and Jérôme P., as well as by material evidence. Moreover, the practices of chasing and endangerment described by Hervé correspond to those documented in the Hautes-Alpes as being recurrent at that time, which makes his testimony all the more plausible and credible.

Although we cannot prove definitively what the chain of events leading to Blessing’s death was, our questioning of the findings of the investigation as well as the new elements that we bring to the understanding of the events justify the request to reopen the investigation, which alone will be able to provide a definitive confirmation of the facts and determine who is responsible for Blessing’s death.

Shedding light on the conditions that led to Blessing’s death is first and foremost essential for her family. According to Christiana Obie, Blessing’s older sister, until her quest for truth and justice is successful, Blessing “will continue to scream”.

Hervé S., on the other hand, explains what is at stake in this counter-investigation, beyond the case of Blessing’s death: “We, the immigrants at the border, are treated like animals. Blessing is not the first time. Maybe a lot of things will be covered up, there are many other people who have been in the same situation. And I wouldn’t like it if tomorrow, the day after tomorrow, it happens again to others who will arrive.”

Indeed, as we have shown, deaths of people migrating through the Alps are recurrent. Since 2015, 46 cases have been documented at the French-Italian border. However, until today, no actor has been held responsible for these deaths. It is also because of this impunity that practices of control that endanger the lives of people whose mobility is illegalized are perpetuated and the list of deaths continues to grow. Four years after the event, as the family and Tous Migrants continue to demand truth and justice for Blessing, honouring this request would be an important step in ending this impunity, and in ending deadly border control practices.

Research team

Border Forensics

Research directors: Charles Heller and Lorenzo Pezzani

Research: Sarah Bachellerie (doctoral researcher, laboratoire Pacte and Université Grenoble Alpes), Cristina Del Biaggio (Professor and researcher, laboratoire Pacte and Université Grenoble Alpes)

Cartography and animations: Svitlana Lavrenchuk and Giovanna Reder

Preliminary geolocation and remote sensing: Santiago Rivas Sola

Key partners of the project

Photogrammetry: Nicolas Robinet (Laboratoire Pacte)

3D Animation: Alican Akturk

Audio analysis: Pau Santamaria, Eduardo Manzano, Jack Naumann and Grant Waters de Anderson Acoustics

Sound design: Zelig Sound

Documentary image and camera work: Frédéric Choffat

Production assistant: Robin Chappatte

Audio recording: Clara Alloing

Documentary image editing: Amanda Cortes

Sound mixing: Martin Stricker and Clive Vella

Voiceover: Sanjana Varghese

Transcription: Zeno Roux-Lafaye

Translation: Isabelle Saint-Saëns, Mélanie Phillipe, Janina Pescinski

Acknowledgements

This Border Forensics analysis was made possible by the contributions of many actors.

First of all, we would like to thank: Tous Migrants, with whom we collaborated intensively in this investigation and without whom this counter-investigation would not have been possible; Hervé S., whose testimony constituted a crucial step forward in the search for the truth; Blessing’s sisters, Christiana Obie and Happy Matthew, through whom we were able to get a glimpse of Blessing Matthew’s personality and life.

For their contribution to our understanding of the conditions of the Durance River and its influence in Blessing’s death, we thank Salvador Navarro-Martinez and Giorgio Manni (Gruppo Sub Verzasca, Switzerland).

For their contributions to the production of the Alpine border deaths database, we thank: Filippo Furri, Uršula Čebron Lipovec, Marijana Hameršak, Geert Arts, Davide Rostan, Piero Gorza.

For the statistics on the arrivals in Briançon and the state of health of the people who crossed the French-Italian border, we thank Chloé Lecarpentier, Agnès Peltier, Refuges Solidaires.

For sharing their expertise on forensic techniques, we thank: Christina Varvia, Nickolas Masterton, Ariel Caine, Francesco Sebregondi, Stefanos Levidis, Mark Nieto, Avi Varma.

This counter-investigation is dedicated to the memory of Blessing and all those who have been victims of violence at Alpine borders.

Press Coverage

30.05.2022 | fr | Mediapart

Mort de Blessing, 20 ans, à la frontière : un témoin sort de l’ombre pour accuser les gendarmes

30.05.2022 | fr | Mediapart

Mort de Blessing Matthew : les gendarmes mis en cause

30.05.2022 | fr | France Info

Mort d’une jeune migrante dans les Alpes : quatre ans après, un nouveau témoignage met en cause la version des gendarmes

30.05.2022 | fr | Dici

4 ans aprés la noyade de Matthew Blessing retrouvée dans la Durance, Tous Migrants demande la réouverture de l’instruction

30.05.2022 | fr | Alpes Sud

Hautes-Alpes : la mort de Blessing Matthew, une affaire judiciaire qui n’est pas si close que ça

30.05.2022 | fr | France 3

Hautes-Alpes : mort d’une jeune migrante à la frontière en 2018, un témoin accuse les gendarmes

30.05.2022 | fr | Dauphiné Libéré

Décès de Blessing Matthew : sa sœur et Tous migrants espèrent relancer l’enquête

30.05.2022 | fr | Dauphiné Libéré

Décès de Blessing Matthew en 2018 : “La seule chose que je veux, c’est la justice”

30.05.2022 | fr | BFM TV (local antenna)

Mort d’une Nigériane, noyée dans les Hautes-Alpes: demande de réouverture de l’enquête

30.05.2022 | it | Redattore Sociale

Blessing e le altre vittime di confine: così la frontiera uccide tra Italia e Francia

31.05.2022 | fr | France Inter

Un petit soldat ukrainien en peine de coeur et épuisé par la boue des tranchées a renoncé à vivre, le Figaro.

31.05.2022 | fr | La Provence

Immigration : ils demandent justice pour Blessing, morte dans la Durance

31.05.2022 | fr | Ouest France

Mort d’une exilée nigériane dans les Alpes : un témoignage inédit mettrait en cause les gendarmes

31.05.2022 | fr | Le Courrier de l’Atlas

Mort d’une migrante à la frontière franco-italienne : un nouveau témoignage conteste la version des gendarmes

31.05.2022 | fr | Ram 05 – Radio Libre

Mort de Blessing Matthew : les parties civiles annoncent avoir obtenu un témoignage inédit

31.05.2022 | fr | Nouvel Obs

Quatre ans après la mort d’une exilée nigériane dans les Alpes, une réouverture de l’enquête demandée

31.05.2022 | it | Carta di Roma

Blessing e le altre vittime di confine: così la frontiera uccide tra Italia e Francia

01.06.2022 | fr | L’Humanité

Révélations accablantes sur la mort de Blessing

01.06.2022 | it | Altreconomia

Le nuove prove sulla morte di Blessing Matthew al confine italo-francese

02.06.2022 | FR | Alp’ternatives

La mort neuve de Blessing Matthew

03.06.2022 | FR | Basta!

Mort d’une exilée à la frontière franco-italienne : un témoignage pointe la responsabilité des forces de l’ordre

Funders