The multimedia feature presenting the results of our investigation is available here: https://www.hrw.org/video-photos/interactive/2022/12/08/airborne-complicity-frontex-aerial-surveillance-enables-abuse

Over the last year, we have partnered with Human Rights Watch to investigate the use by the EU’s border agency, Frontex, of aerial surveillance in the central Mediterranean. The aircraft, several planes and a drone operated by private companies, transmit video feeds and other information to a situation centre in Frontex headquarters in Warsaw, where operational decisions are taken about when and whom to alert about migrants’ boats. Frontex aerial surveillance is key in enabling the Libyan Coast Guard to intercept migrant boatsand return their passengers to Libya, knowing full well that they will face systematic and widespread abuse when forcibly returned there.

To circumvent Frontex’s lack of transparency on these issues (in processing 27 of 30 freedom of information requests we submitted – the others are pending – Frontex identified thousands of relevant documents but released only 86 of them, most of which were heavily redacted) we cross-referenced official and open-source data, including drone and plane flight tracks, together with information collected by Sea-Watch (through its various search and rescue ships and planes operating in the area), the Alarm Phone, as well as the testimony of survivors who courageously shared their stories with us.

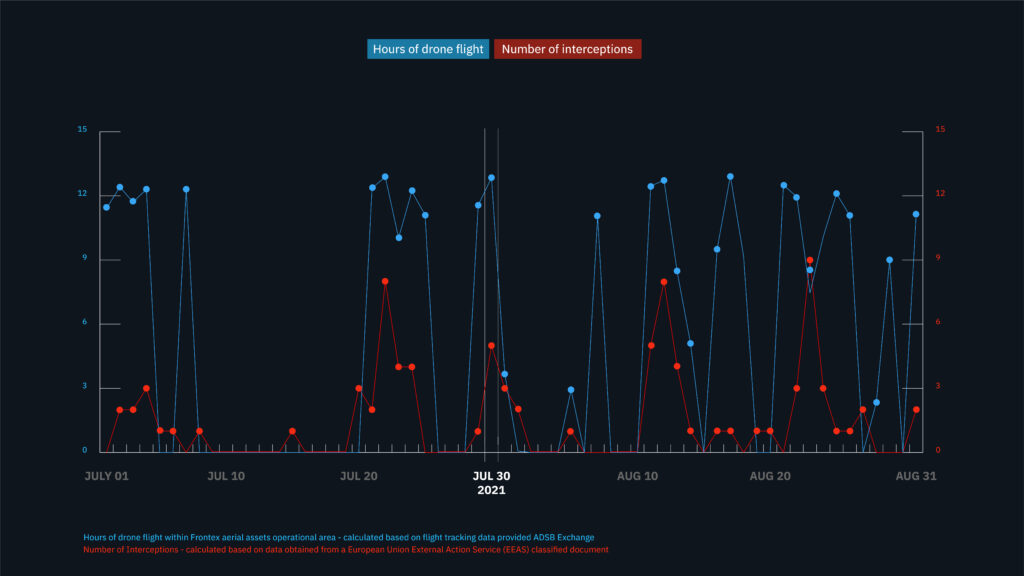

Overall, contrary to Frontex claim that its aerial surveillance saves lives, the evidence gathered by Human Rights Watch and Border Forensics demonstrates it is in service of interceptions by Libyan forces, rather than rescue. While the presence of Frontex aircraft has not had a meaningful impact on the death rate at sea, we found a moderate and statistically significant correlation between its aerial assets flights and the number of interceptions performed by the Libyan Coast Guard. On days when the assets fly more hours over its area of operation, the Libyan Coast Guard tends to intercept more vessels.

Our reconstruction of the events of July 30, 2021, when several boats carrying migrants were intercepted by the Libyan Coast Guard in the area where the drone was patrolling, is a good demonstration of this. The evidence we collected strongly suggests that the droneplayed a key role in facilitating the interception of potentially hundreds of people.

The analysis of available data supports the conclusion that the Frontex aerial surveillance forms a central plank of the EU’s strategy to prevent migrants and asylum seekers from reaching Europe by boat and to knowingly return them to unspeakable abuse in Libya. It should be understood in continuity with the progressive withdrawal of EU ships from the central Mediterranean, the handover of responsibility to Libyan forces, and the obstruction of nongovernmental rescue groups which we have been investigating in the frame of the Forensic Oceanography project since several years.

The retreat of rescue vessels from the central Mediterranean and the simultaneous increase of surveillance aircraft in the sky is yet another attempt by the EU to further remove itself spatially, physically, and legally from its responsibilities: it allows the EU to maintain a distance from boats in distress, while keeping a close eye from the sky that enables Libyan forces to carry out what we have previously referred to as “refoulement by proxy”. Our investigation seeks to re-establish the connection between Frontex aerial surveillance and the violence captured migrants face at sea and in Libya thereafter.

Reconstructing 30 July 2021

Since the beginning of our research, we have been looking into a number of specific cases of interceptions that involved European aerial assets. Thanks to the relentless effort of documentation by civil society organisations active in the central Mediterranean, in particular the Alarm Phone and Sea Watch, we were able to put together an extensive list of such cases.

We eventually decided to focus on the events of July 30, 2021 as a case study. In order to reconstruct what happened on that day, we have combined witness testimonies, data and footage collected by Alarm Phone and Sea Watch, tracks of aerial and naval assets, open-source information and data about disembarkation in Libya as well as two separate databases of interceptions (Frontex’ own JORA database and information from two European Union External Action Service classified documents).

Frontex drone’s tracks that day indicate it most likely detected at least two boats later intercepted by the Libyan Coast Guard. The rescue ship Sea-Watch 3 witnessed by chance the interception of one of them that took place within the Maltese Search and Rescue Area. The Sea-Watch 3 had not received any distress alert via Frontex despite being in the immediate vicinity of the boat and ready to assist its passengers.

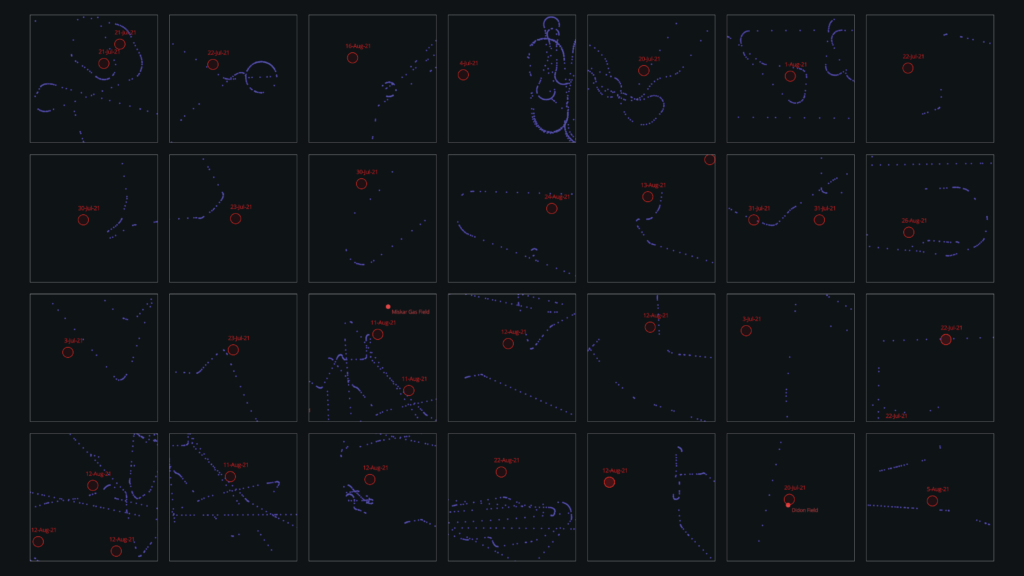

Frontex’ own database admits that its aerial surveillance program detected a total of 5 boats on that day. While only further disclosure by Frontex would allow to ultimately assess its impact on each specific interception that took place on that day, the precise geographical coordinates for the five interceptions reported in the classified EEAS documents seem to match at least three peculiar flight patterns of the Frontex drone.

Analysing Frontex aerial surveillance

Flight tracking

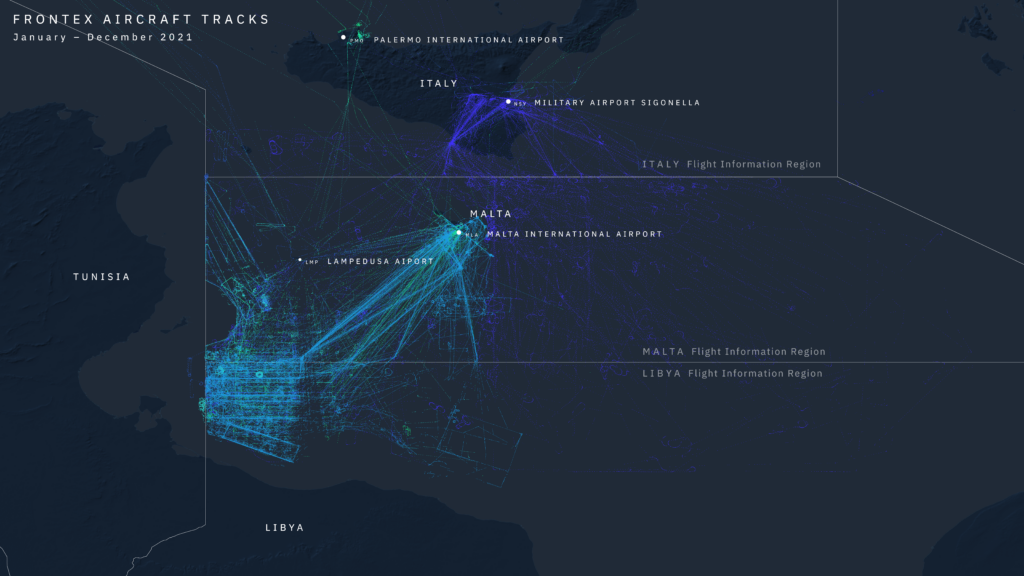

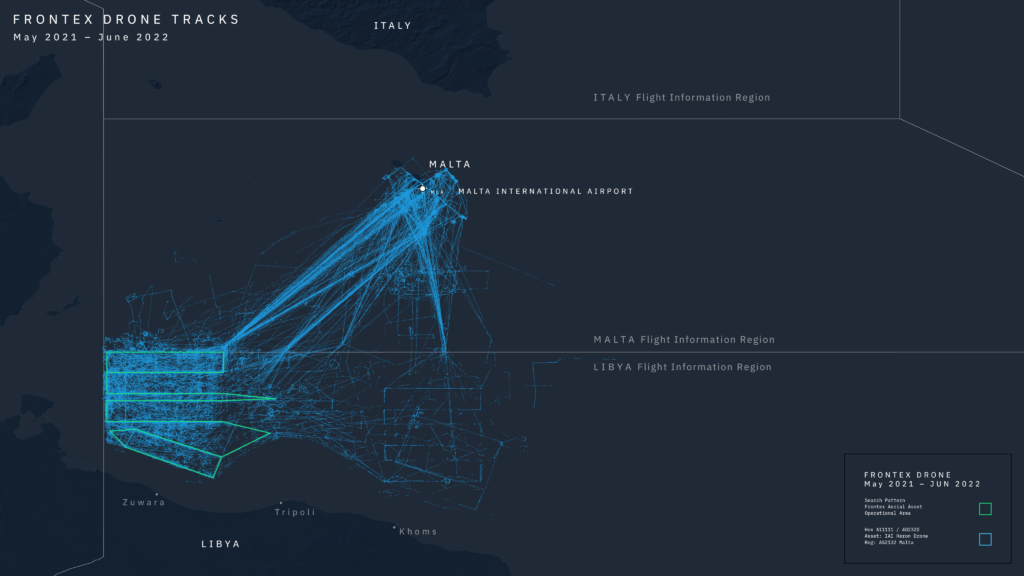

In parallel to case reconstructions, we have been tracking the overall activities of Frontex aircraft in the central Mediterranean. Since these planes and drone are chartered from private companies such as DEA Aviation and ADAS, a subsidiary of Airbus, there is no publicly available official list of such assets. The first task was to understand which were the aerial assets patrolling the central Mediterranean on behalf of Frontex. Cross-referencing various identification information (hexcodes, callsigns, etc.) of these planes with those that had been already identified by Sea Watch airborne team and various journalists allowed us to establish a dependable list of Frontex aerial assets operating in the area.

Once that was established, we acquired from ADS-B Exchange (the only flight tracking platform that does not block any aircraft for which data is received by their feeders) a large dataset of flight tracking data covering a period of several months (May 2020 to September 2022) for all these aircraft. While the low number of data feeders near our area of interest means that coverage of the recorded data is at times inconsistent, ADS-B flight tracking data (which include latitude, longitude, altitude, and several other parameters) provide an exceptional insight into aerial activities performed by these assets and became a key element in our investigation.

Thanks to these data, we were able to visualize the extend of each assets operational area over time. Each of these aircraft monitors a specific area of the central Mediterranean. What emerged were also a series of clearly identifiable and consistent search patters that Frontex aircraft are flying off the coast of Libya. More generally, these visualisations have allowed to grasp the extensive, yet tightly knit web of surveillance that results from aerial operations.

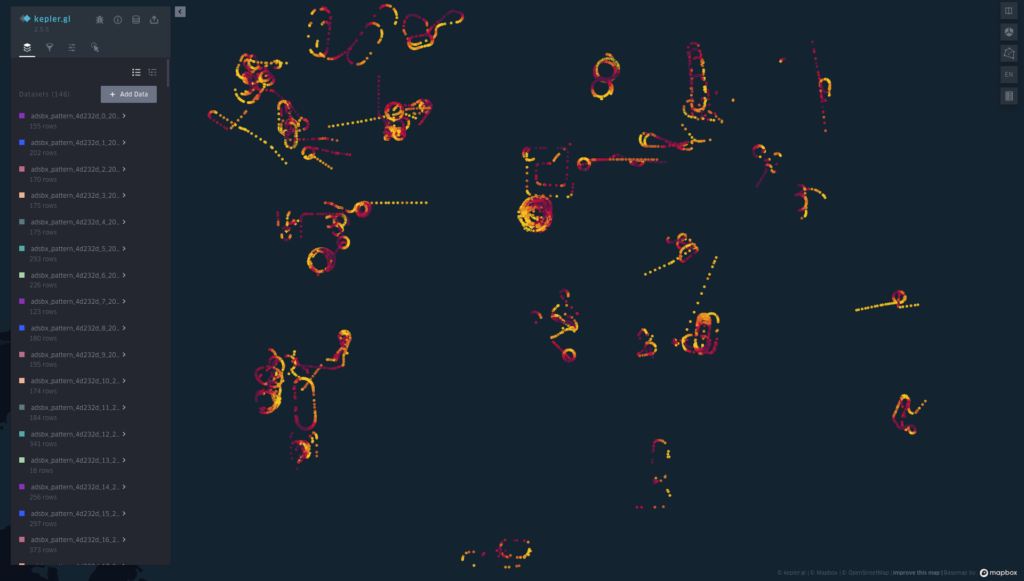

Pattern analysis

When observed closely, flight tracks can provide further precious insights into Frontex surveillance activities. Several loops, U-turns, perfect circles, and sharp corners starts to emerge against the strict geometry of standard search patterns. These deviations indicate an aircraft is taking a closer look at something, thus testifying to potential sightings of migrant boats. Inspired by similar projects by John Wiseman, Emmanuel Freundenthal and others, we then started to isolate and taxonomise such search patterns and then wrote code to automatically identify similar patterns across the whole flight tracking dataset we had acquired. While this aspect of the research is still ongoing, it was already very useful in reconstructing the events of July 30, 2021, as detailed in the following section.

Statistical analysis

In order to assess the overall impact of aerial surveillance, we also conducted statistical analysis exploring the relation between interceptions carried out by Libyan forces and the presence of Frontex’s aerial assets in the 2021-2022 timeframe.

We first compiled several statistical data sources (data from the IOM, the UNHCR, the Maltese government as well as Frontex’ JORA database and a classified report by the European External Action Service) which, despite inconsistencies, have allowed us to measure migrant crossings and deaths, Libyan Coast Guard interceptions, and Frontex aerial presence.

The data gathered shows that Frontex aerial surveillance activities have intensified over time, and that they have been increasingly related to interception events. Our analysis reveals that almost one third of the 32,400 people Libyan forces captured at sea and forced back to Libya in 2021 were intercepted thanks to intelligence gathered by Frontex through aerial surveillance. Frontex incident database also shows that while Frontex’s role is very significant in enabling interception to Libya, it has very little impact on detecting boats whose passengers are eventually disembarked in Italy and Malta.

We then tested the correlation between Frontex aerial presence and Libyan Coast Guard interceptions over time and in space. The results show a moderate-to-strong and statistically significant correlation between the number of interceptions and the hours of flight flown by Frontex aerial assets. Said otherwise, on days when the assets fly more hours over its area of operation, the Libyan Coast Guard tends to intercept more vessels. A spatial approach showed that interceptions and flight tracks are autocorrelated in space. At the same time, contrary to Frontex claims that aerial surveillance saves lives at sea, the analysis shows that there is no correlation between death rate and the flight time.

Read the full statistical analysis here

Conclusion

Ultimately these different methods have allowed us to demonstrate how Frontex aerial surveillance (and in particular, because of its wider operational range, its drone) has become a key cog in the “pushback machine” that forces thousands of people back to abuse in Libya.

The publication of our findings with Human Rights Watch is the first stage of our ongoing investigation into the impact of European aerial surveillance on the lives and rights of migrants. We plan to continue deepening this investigation over the coming months.

Research team

Border Forensics

Research directors: Charles Heller and Lorenzo Pezzani

Research: Giovanna Reder, Kiri Santer

Cartography and animations: Jack Isles, Svitlana Lavrenchuk and Rossana Padeletti

Pattern Recognition: Luca Obertüfer

Statistical Analysis: Stanislas Michel

Human Rights Watch

Judith Sunderland, Giulia Tranchina, Julia Link, Grace Choi and John Emerson

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Sea Watch and the Alarm Phone for generously sharing their data with us.

We would also like to thank Emmanuel Freudenthal, Arthur Carpentier, Sergio Scandura, Itamar Mann, Dan Streufert, Luisa Izuzquiza, Matthias Monroy, and Dan Gettinger for sharing their expertise and the University of Chicago Global Human Rights Clinic for their support. Flight tracks have been purchased from ADS-B-Exchange.

Funding

Border Forensics’ work on this projects has been supported by the Robert Bosch Foundation, Stiftung Pro Asyl, Karl Popper Foundation, The David and Elaine Potter Foundation, The Fund for Global Human Rights, Investigative Journalism for Europe, Safe Passage Foundation, Stiftung Temperatio, Canton de Genève, Ville de Genève

Lorenzo Pezzani’s work on this project has been funded by the European Research Council (HEMIG, grant agreement 101042338)

Press Coverage

12.12.2022 | fr | Le Journal de l’Afrique

L’Agence européenne Frontex, complice des abus contre les migrants ?

12.12.2022 | it | La Repubblica

“Frontex è complice degli abusi in Libia”: la sorveglianza aerea facilita le intercettazioni dei migranti, il loro respingimento e il ritorno alle violenze

12.12.2022 | en | The Libya Update

Human Rights Watch: EU’s Frontex complicit in migrant abuse in Libya

12.12.2022 | de | nd aktuell

EU-Luftaufklärung für Libyen

12.12.2022 | it | Africa Revista

Libia, agenzia dell’Unione europea complice negli abusi sui migranti secondo Hrw

12.12.2022 | en | Reuters

EU’s Frontex ‘complicit’ in forced migrant returns to Libya – HRW

12.12.2022 | spa | Notimérica

Libia.- HRW acusa a Frontex de ser “cómplice” de los “abusos sistemáticos” cometidos en Libia contra los migrantes

12.12.2022 | en | Security Architectures in the EU

EU aerial surveillance for Libya makes Tripoli coastguard doing the „dirty work“

12.12.2022 | fr | cameron actuel

L’Agence européenne Frontex, complice des abus contre les migrants ?

13.12.2022 | it | Il Manifesto

I droni di Frontex coordinano le milizie libiche

13.12.2022 | en | AP News

Rights group claims EU ‘complicit’ in Libya’s migrants abuse

13.12.2022 | en | The Shift

Frontex drone and planes out of Malta ‘complicit in human rights abuses’

13.12.2022 | en | Libya Observer

Human Rights Watch: EU complicit in abuse in Libya

13.12.2022 | en | The New Arab

EU ‘complicit’ in human rights abuses in Libya: new report

13.12.2022 | fr | Infomigrants

Migrants en Méditerranée : pour Human Rights Watch, Frontex est “complice” des garde-côtes libyens

13.12.2022 | en | Infomigrants

Human Rights Watch: EU agency ‘complicit’ in migrant abuse in Libya

13.12.2022 | en | Are You Syrious

AYS News Digest 12/12/2022

13.12.2022 | en | euobserver

Over 4,000 Frontex documents published by German NGO

14.12.2022 | en | Business & Human Rights Resource Center

Libya: HRW reports use of aerial surveillance tech. makes EU border agency “complicit” in abuse of migrants while avoiding duties under intl. law

14.12.2022 | en | Aljazeera

Frontex delivers cruelty from the skies

16.12.2022 | en | European Council on Refugees and Exiles

EU Southern Borders: Deaths Off Spain and Morocco as Amnesty Denounces the Failure to Ensure Justice for Melilla Victims, More Than 500 Survivors Disembark in Italy, Frontex Facilitates Interception and Return to Libya

18.12.2022 | de | Frontex Investigation

Human Rights Watch Bericht: Frontex-Luftüberwachung soll Pull-Backs nach Libyen fördern