Summary

On 30 August 2021, Roger Nzoy Wilhelm, a 37-year-old Black Swiss and South African man, was killed by the police at Morges railway station, Switzerland. Four years after the event, and following two failed attempts by the public prosecutor to close the case, neither truth nor accountability have been established. At the request of Nzoy’s family, Border Forensics, in collaboration with the Independent Commission of Inquiry on the Death of Roger Nzoy Wilhelm, has conducted a counter-investigation. While Border Forensics has to date focused on the continuum of border violence that affects the trajectories of migrants, this investigation focuses on the violent policing of the boundary of race and the way it materialises within societies. Our analysis of the circumstances of Nzoy’s death demonstrates that while he was in psychological distress, the police officers’ inaccurate and biased perception of him as a threat led them to prioritise the use of lethal force over assistance and care. We further locate Nzoy’s killing in relation to other cases of police-related deaths in Switzerland and analyse the structural conditions that have enabled them. We conclude that the othering of Nzoy, including his racialisation as a “man of colour” read in combination with his masculinity and psychological distress, shaped the police response that led to his death.

This report addresses incidents of violence that may be distressing. We invite readers to approach the content with care.

Introduction

On 30 August 2021, Roger Michael Wilhelm, 37, was shot and killed by a police officer at the railway station of Morges, a municipality in the Canton of Vaud, Switzerland. A Black Swiss and South African man born and raised in Zurich, Roger chose to go by the name Nzoy from an early age – reflecting his close ties to his family’s cultural heritage. His close ones describe him as a writer, a musician and a practising Christian. While he proudly identified as a Black man, being Black in Switzerland exposed Nzoy to racial discrimination, including racial profiling by the police.

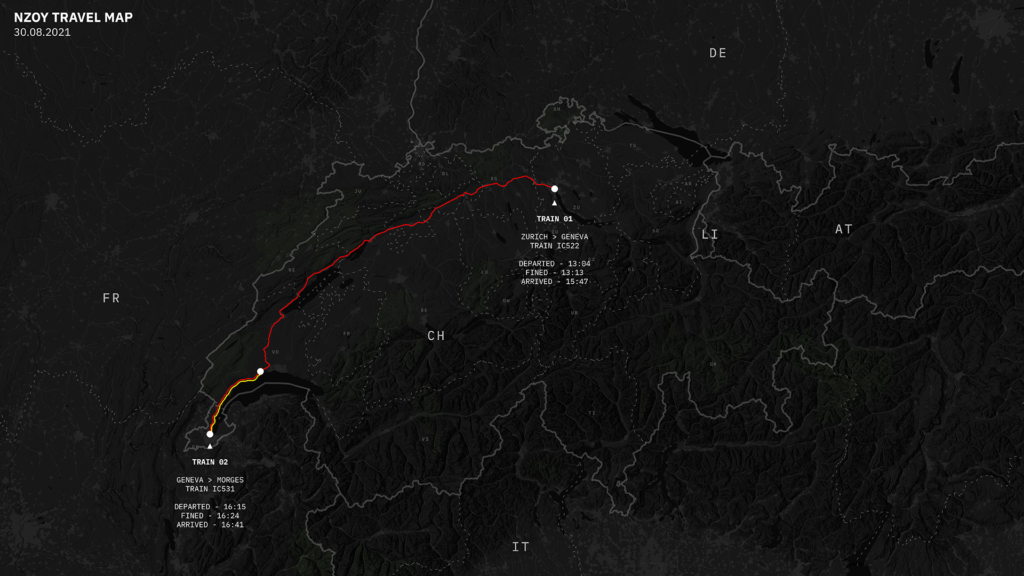

Nzoy had been briefly hospitalised less than a week before his death with suspected paranoid schizophrenia. The morning of his death, he presented himself to the Emergency Department at the University of Zurich Hospital during a suspected psychotic episode. After an initial neurological assessment, which identified the need for further examination but did not determine that he was a risk to himself or others, Nzoy left the hospital independently. Later that day, for reasons that are still unclear, he boarded a train in Zurich for Geneva where he arrived at 15:47. He then took a train in the opposite direction and got off in Morges at 16:41.

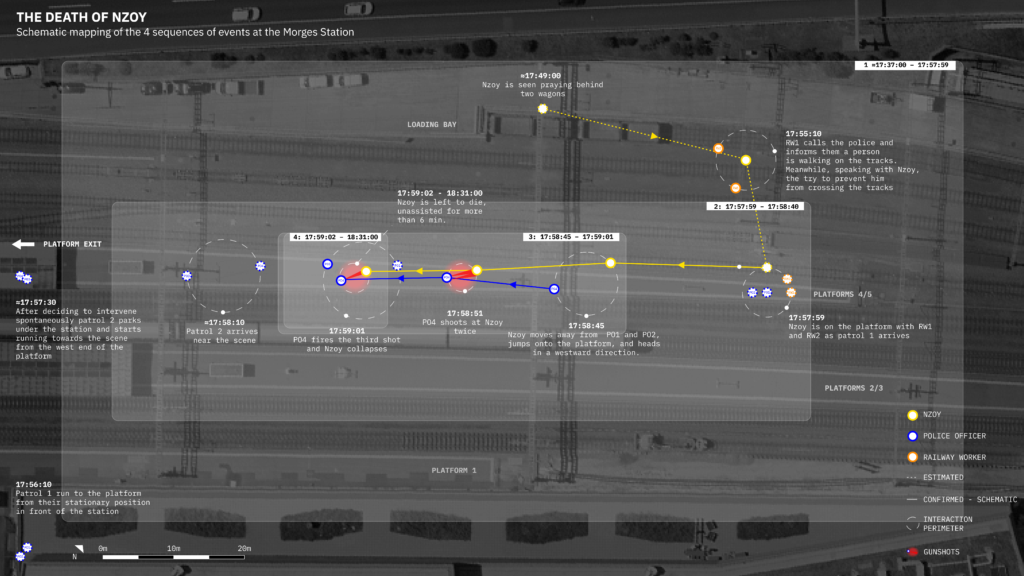

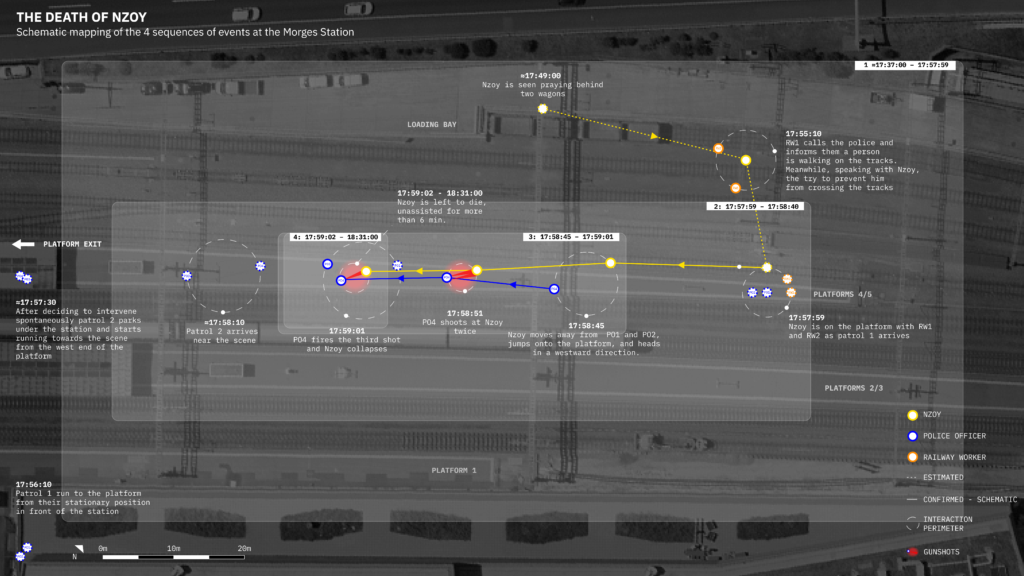

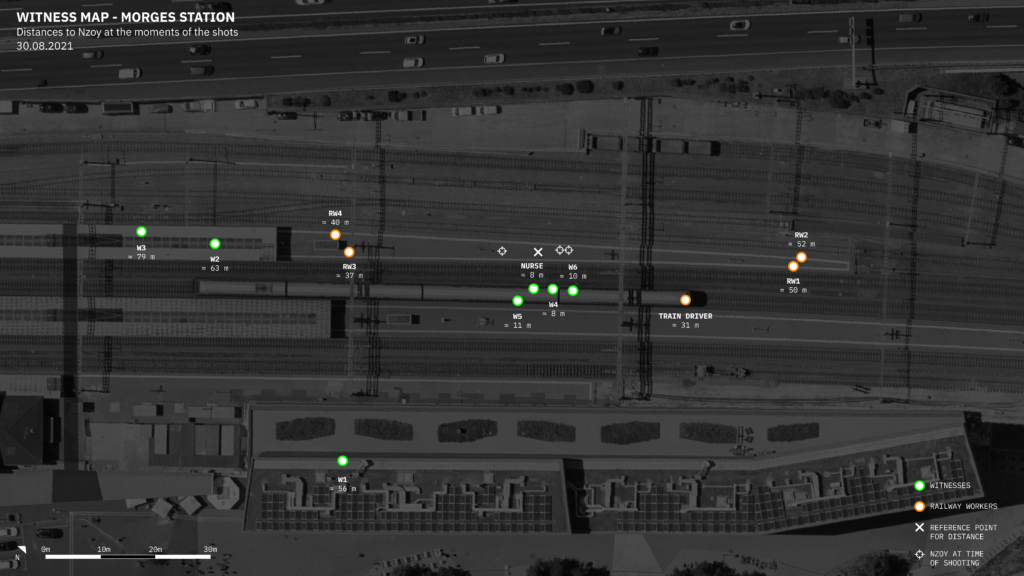

At Morges station, railway workers reported seeing Nzoy praying on a loading platform and crossing train tracks. According to his close friends and family, praying was a way for Nzoy to regain balance in situations of distress. Two railway workers first came into contact with him, talking to him, trying to calm him down, to prevent him from walking on the tracks, asking him “not to act crazy”. One of them called the police at the same time. A first police patrol arrived at the request of a police dispatcher – composed of police officer 1 (PO1) and police officer 2 (PO2) – at 17:58. Then, moments later, a second patrol intervened spontaneously – composed of police officer 3 (PO3) and police officer 4 (PO4). When the second patrol arrived, the four police officers semi-circled him and the situation escalated within seconds.

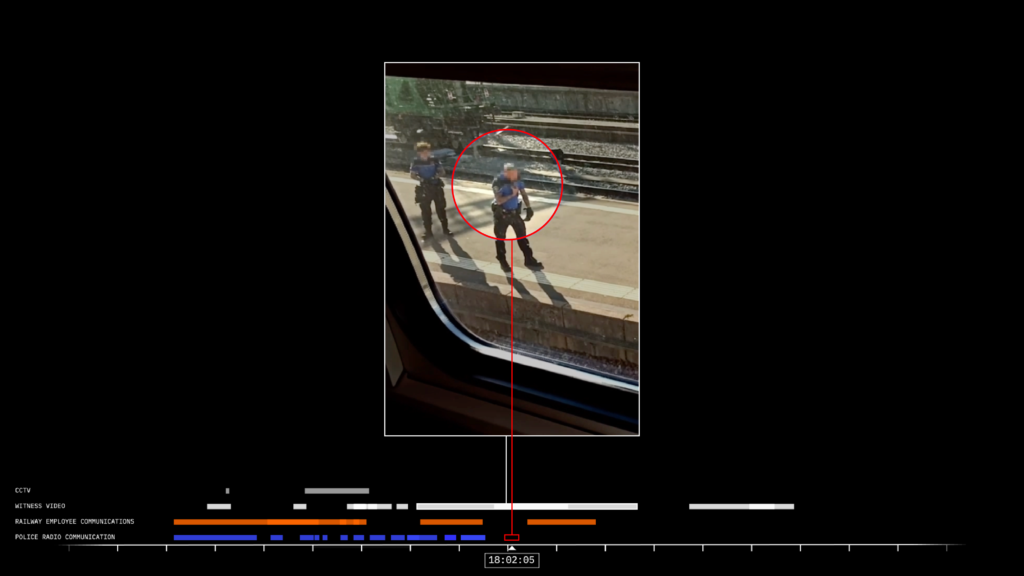

Since a train had to be held at the station platform due to the unfolding events, several passengers as well as local inhabitants witnessed and filmed the scene. Witnesses’ videos show Nzoy moving away from Patrol 1, stepping from the tracks onto the platform and running in a westward direction, from where Patrol 2 was approaching. Facing him, PO4 shot twice, with one bullet most likely grazing the back of Nzoy’s right hand and another striking him in the left groin. Nzoy fell down and rolled as he hit the ground. He stood up again, resumed running, and was shot by PO4 a third and final time with a bullet most likely striking him on the left flank.1The medical forensic report commissioned by the public prosecutor and conducted by the University Center of Legal Medicine Lausanne-Geneva, noted three wounds but did not clarify the chronology of the shots despite numbering the wounds from 1 to 3. The report states that wound 1 is intra-abdominal, with an entry point on the left flank and a projectile found in the right internal oblique muscle. Wound 2 is located on the left inguinal region and a projectile lodged in the left acetabulum. Wound 3 is on the back of Nzoy’s right hand, suggesting a firearm projectile injury of a tangential nature. Case file, 5004, p. 47 At 17:59, Nzoy collapsed to the ground, and never rose again.

Immediately after the shooting, PO3 informed via radio that shots had been fired. When the dispatcher requested additional information, PO3 responded: “I don’t have more information, a man of colour, he is on the ground.”2“J’ai pas plus d’infos, un homme de couleur, il est au sol” Case file, 1020. During the six minutes that elapsed after the shots, while Nzoy was lying face down on the platform, the police officers handcuffed him behind his back, then put him on his side to search him. They did not enquire into his health nor did they conduct first-aid measures. After six minutes, an off-duty nurse who witnessed the scene intervened spontaneously to provide emergency care, followed by the arrival of emergency services. Nzoy’s death was declared at 18:31, on the platform, in the train station of Morges.

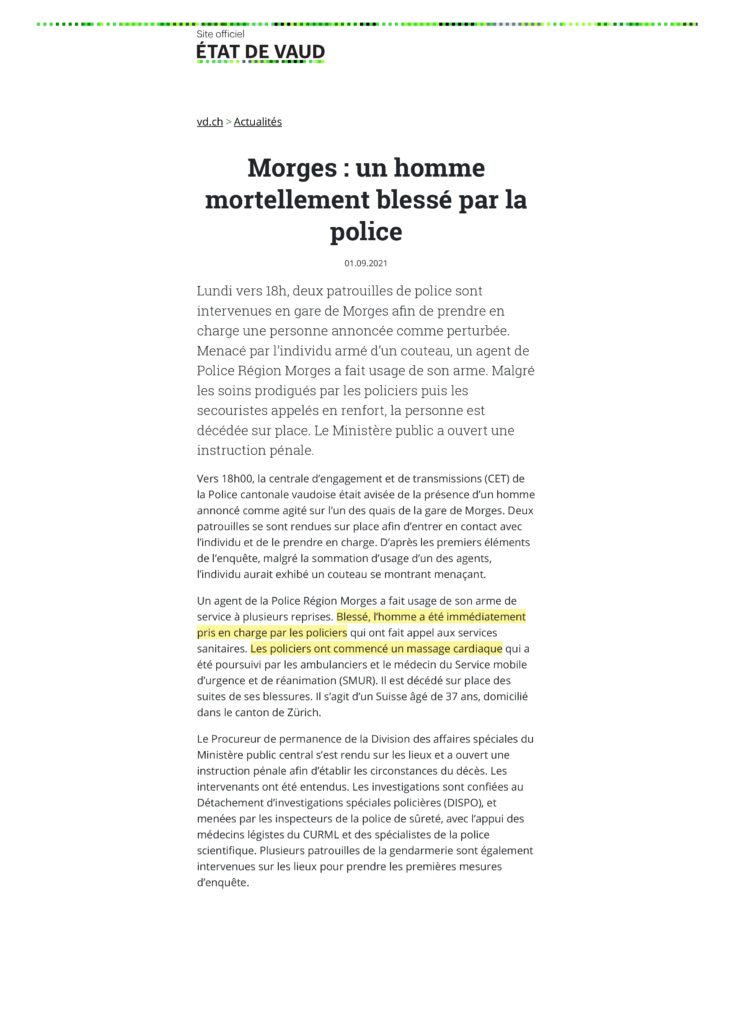

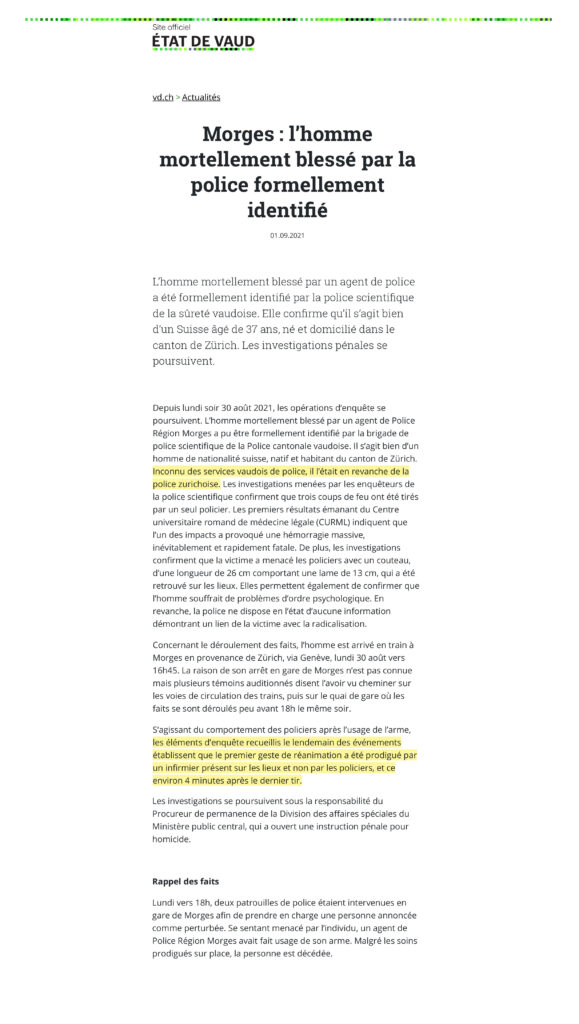

About an hour after the events, local media outlets began publishing videos of the events along with information obtained from witnesses’ testimonies and a press release from the Vaud Cantonal Police.320 Minutes, “La police fait feu à plusieurs reprises, un homme meurt sur le quai,” 20 minutes, August 30, 2021, https://www.20min.ch/fr/story/la-police-fait-feu-sur-un-homme-a-la-gare-de-morges-380390384863. The first press statement disclosed that two police patrols intervened at Morges station to respond to a “disturbed” individual. It further stated that, threatened by the individual armed with a knife, an officer from the Morges Regional Police used his firearm and, despite receiving care from the police officers and then from paramedics, the person died at the scene.4État de Vaud, “Morges : un homme mortellement blessé par la police,” September 1, 2021, https://www.vd.ch/actualites/actualite/news/14888i-morges-un-homme-mortellement-blesse-par-la-police. Two days after the events, another press statement was released. It gave additional information about the knife discovered at the scene, added that the person was already known to the Zurich police and corrected the initial statement by specifying that the first resuscitation effort was made by a nurse present at the scene rather than the police officers.5État de Vaud, “Morges : l’homme mortellement blessé par la police formellement identifié,” September 1, 2021, https://www.vd.ch/actualites/actualite/news/14892i-morges-lhomme-mortellement-blesse-par-la-police-formellement-identifie.

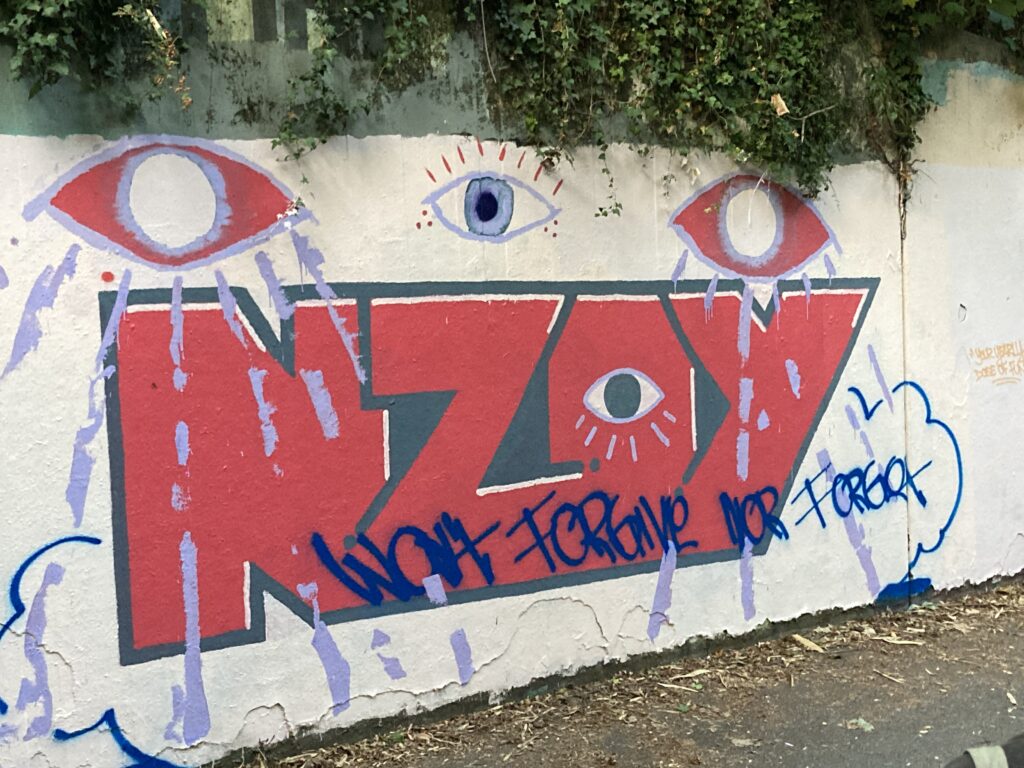

Though the criminal investigation had only just begun, the tone of these press statements was already conclusive. Their description of the events legitimised the fatal shooting carried out by PO4 through the assertion that he was acting in self-defence while threatened with a knife by a mentally unstable person who was known to the police. This narrative was widely spread by the media and supported by the Morges police.6Antoine Hürlimann, “L’homme abattu à Morges se ruait sur les policiers,” Suisse, Blick, September 1, 2021, https://www.blick.ch/fr/suisse/une-video-exclusive-le-montre-lhomme-abattu-par-la-police-a-morges-se-ruait-sur-les-agents-id16796148.html; 20 Minutes, “Coups de feu en gare de Morges (VD) – La version de la police confirme celle des témoins,” 20 minutes, September 1, 2021, https://www.20min.ch/fr/story/homme-tue-par-un-policier-trois-balles-ont-ete-tirees-677743935687; ArcInfo, “Morges: l’homme décédé sur les quais de la gare souffrait de troubles psychologiques,” ArcInfo, September 1, 2021, https://www.arcinfo.ch/suisse/morges-lhomme-decede-sur-les-quais-de-la-gare-souffrait-de-troubles-psychologiques-1105410; Raphaël Cand, “«Aucun policier ne souhaite vivre ça»,” Journal de Morges, September 2, 2021, https://journaldemorges.ch/actualite/aucun-policier-ne-souhaite-vivre-ca Four years after the killing of Nzoy, and after two failed attempts from the public prosecutor to close the criminal investigation and abandon the proceedings, Nzoy’s family and close ones continue to oppose this conclusion and argue that Nzoy would not have been treated in such a violent manner had he been white.

At the request of Nzoy’s family, Border Forensics, in collaboration with the Independent Commission of Inquiry on the Death of Roger Nzoy Wilhelm (hereinafter “Independent Commission”),7The Independent Commission of Inquiry on the Death of Roger Nzoy Wilhelm is a group of experts constituted by Nzoy’s family. It is composed of lawyers, psychologists, physicians, sociologists, political scientists, anthropologists, historians and cultural scientists. They work closely with Nzoy’s family and their lawyer and conduct research and provide expertise on the case to support their demand for truth and justice: https://www.nzoycommission.org/en/wer-wir-sind/ has been conducting a counter-investigation for two years to produce a detailed analysis of the events and answer the following key questions:

- What circumstances and police (in)actions led to Nzoy’s death?

- What are the deficiencies and evidentiary gaps of the criminal investigation?

- To what extent was the killing of Nzoy shaped by racism and processes of othering?

- To what extent are institutions equipped to address demands for truth and justice in cases of police-related death?

Combining Border Forensics’ spatial, visual and geostatistical methods with the interdisciplinary expertise of the Independent Commission, we have reconstructed the complex constellation of factors, extending across different spatial and temporal scales, that culminated in Nzoy’s death. Our counter-investigation reveals fundamental new insights into the events at Morges station, which challenge the findings of and narrative constructed by the criminal investigation. In particular, we demonstrate that Nzoy did not constitute a threat to others and that his shooting was illegitimate. Beyond the case of Nzoy, our report also offers novel insights into police-related deaths in Switzerland – a category we define as including any interaction with law enforcement agents resulting in a civilian’s death. We demonstrate that police-related deaths disproportionately impact people – mostly men – subjected to processes of othering, in particular racialisation. Finally, our analysis indicates that a regime of impunity for police-related deaths has consolidated. As a result, truth and justice are denied to victims and their families and the perpetuation of violent police practices is enabled.

Report outline

To answer our four key questions outlined above, the report is organised into four main chapters, structured by two analytical levels.

The first level focuses on the event of Nzoy’s killing and examines: (1) the evidence concerning the (in)actions of the actors on site that led to Nzoy’s death; and (2) the deficiencies and evidentiary gaps in the criminal investigation.

The second analytical level locates the case of Nzoy’s killing in relation to similar incidents, and analyses the structural conditions that have enabled them. In particular, we focus on: (3) the longer history and broader structures of racism and police-related deaths in Switzerland; and (4) the legal, political and media frameworks that undermine demands for truth and justice and allow for violence to be perpetuated.

Chapter 1 provides a detailed analysis of the circumstances and the (in)actions of all actors who interacted with Nzoy at the Morges train station on 30 August 2021, ultimately causing Nzoy’s death. By cross-referencing evidence contained in the case file to which Nzoy’s family gave us access, in particular videos filmed by witnesses, police radio recordings and transcripts of police hearings, we establish a precise reconstruction of the sequence of events in space and time.

Our reconstruction concentrates on the time frame between 16:41 and 18:31, which we divide into four successive sequences, each of which corresponds to a critical stage in the unfolding of events.

The first sequence focuses on the situation at Morges station before the arrival of the first and second police patrols. Our combined analysis of video and audio recordings of Nzoy’s interactions with two railway workers, transcripts of police hearings as well as psychiatric research reveals that Nzoy exhibited behaviour indicative of a psychiatric disorder with signs of confusion and distress. During this sequence, for which evidence is fragmentary, it appears that both Nzoy and the railway workers were actively looking for resources to manage the unstable situation. There is no indication of escalation.

The second sequence focuses on the arrival of the dispatched first patrol and the spontaneous intervention of the second patrol. Based on video and audio data as well as transcripts of police hearings, our analysis indicates that the arrival of police had a triggering effect on Nzoy linked to his ongoing psychological distress and previous experiences of racial profiling. This combination of factors heightened stress for Nzoy, causing his behaviour to shift from confusion and withdrawal to panic.

The third sequence focuses on the moments immediately leading up to the shooting of Nzoy by the police, and the shooting itself. We reconstruct Nzoy’s trajectory in relation to the officers and assess the alleged presence of a knife in his hands. Our analysis provides crucial new evidence that leads us to refute the criminal investigation’s findings and its narrative according to which Nzoy aimed to attack PO4 with a knife, which in turn has legitimised the officer’s lethal response. Our analysis of this defining sequence unfolds in several steps.

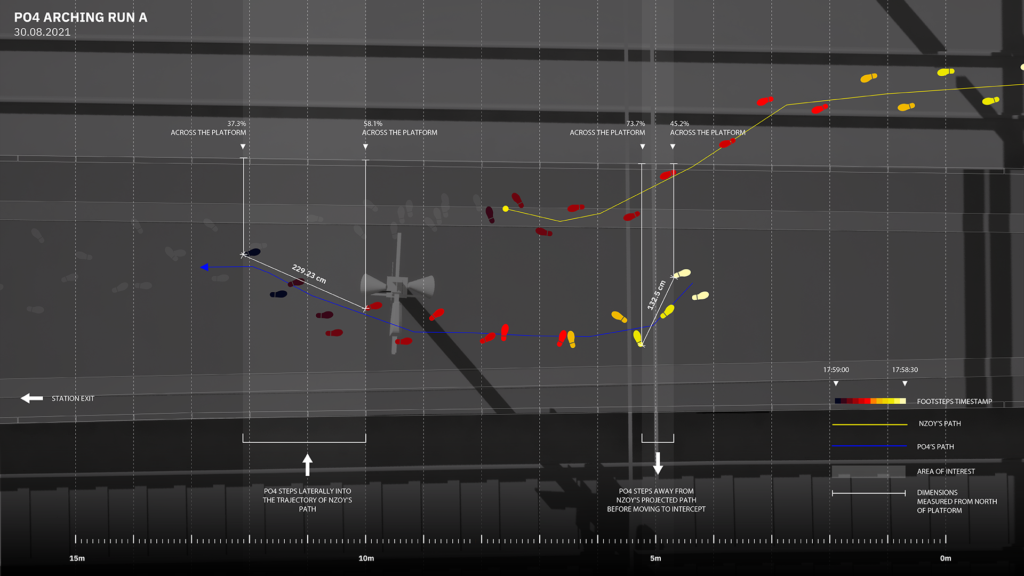

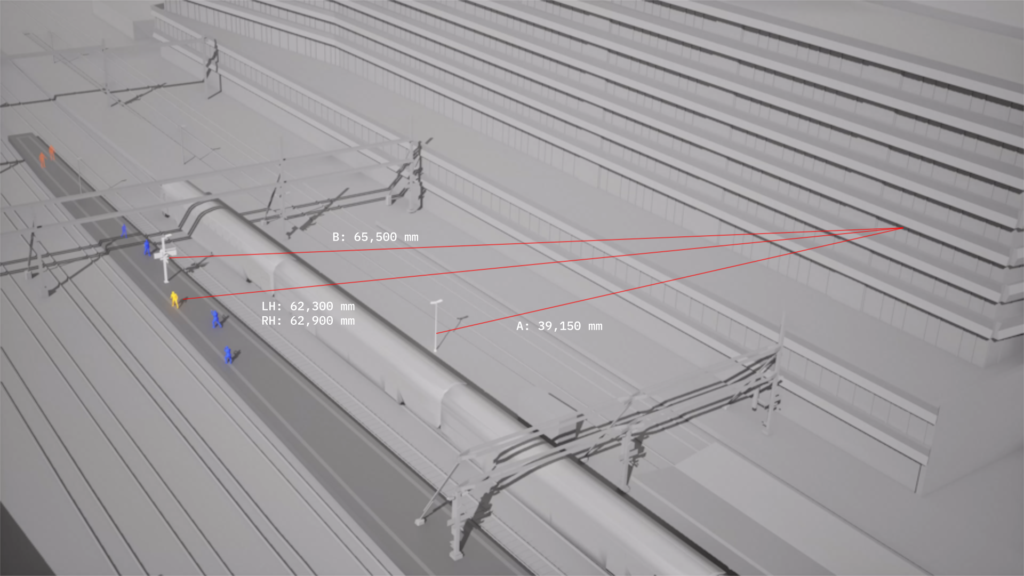

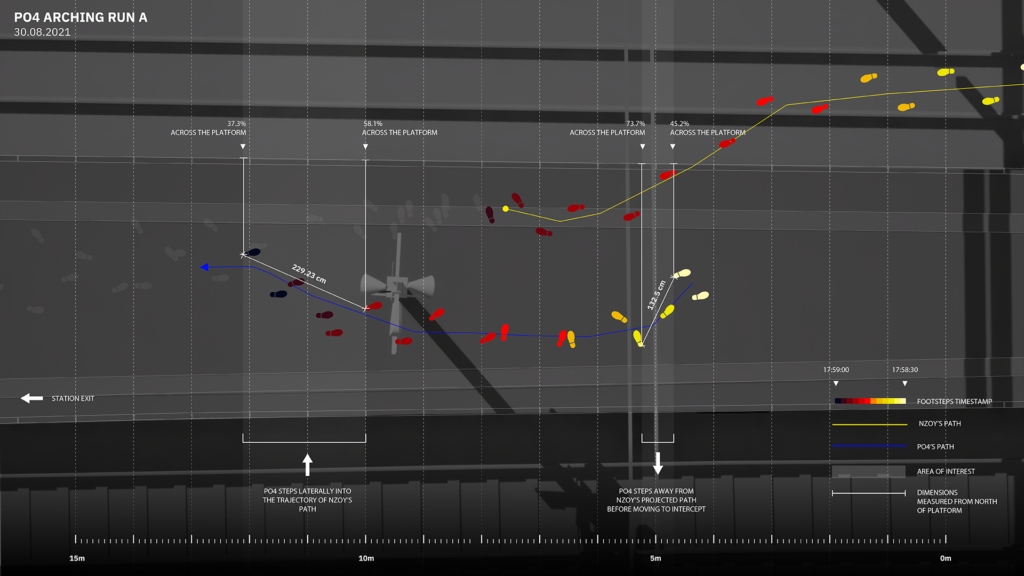

First, by precisely plotting the footsteps of Nzoy and PO4 onto a detailed 2D plan of the platform, we demonstrate that Nzoy’s trajectory of motion was lateral and that PO4 stepped into Nzoy’s projected path, contradicting the narrative that Nzoy was charging or attempting to attack PO4.

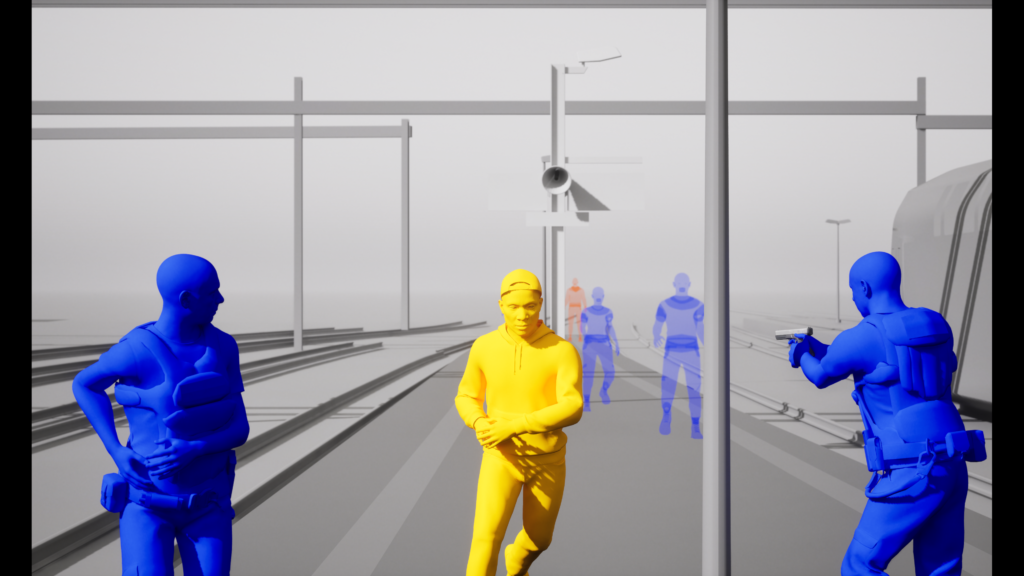

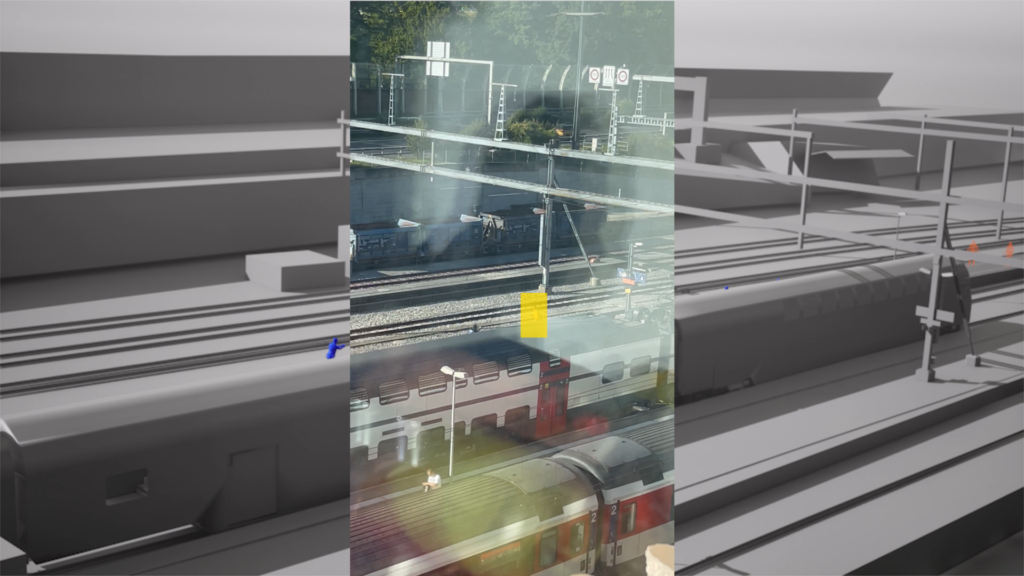

Second, this analysis is supported through the reconstruction of key moments in a virtual 3D environment. Based on video evidence, we were able to precisely recreate the positions of Nzoy and PO4, demonstrating that Nzoy’s path was consistent with defence, confusion and flight rather than aggression and attack.

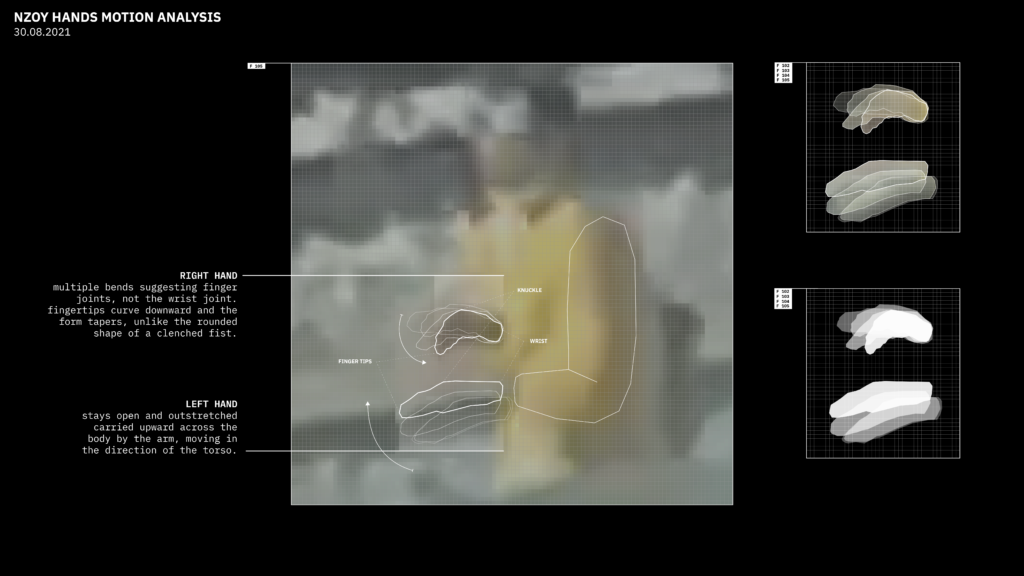

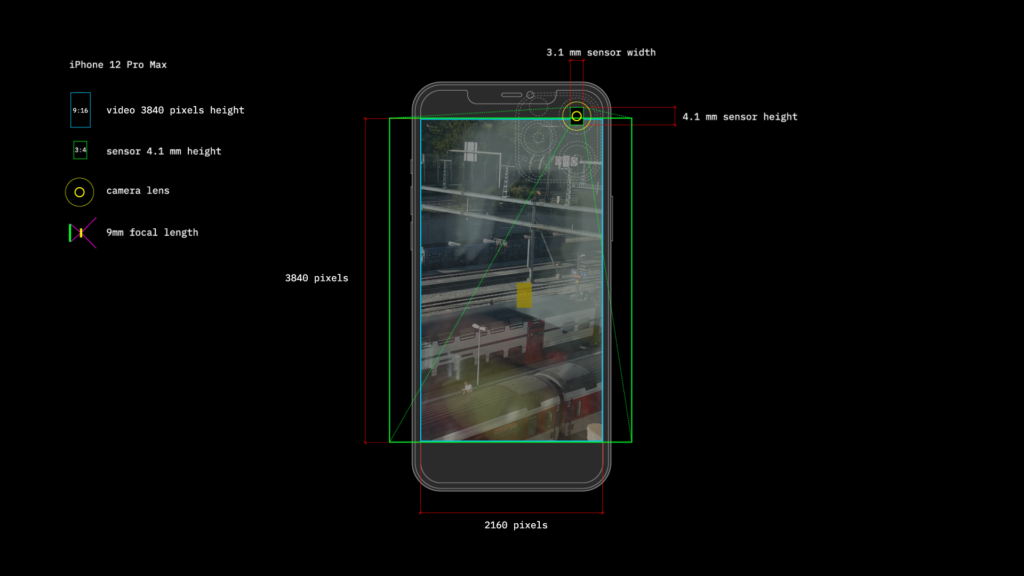

Third and finally, we conducted a spatial analysis of Nzoy’s hands in the moments immediately prior to the first shots fired by PO4. Using a sequence of video evidence recorded from an apartment overlooking the station where both of Nzoy’s hands are clearly visible, a video-pixel analysis allowed us to estimate the real-world size of Nzoy’s hands in the image as well as their shape and motion. Through this analysis, we demonstrate that Nzoy’s hands were open just before the first shots were fired at him. It was thus highly unlikely that he was holding a knife at that moment.

The fourth and last sequence we analyse focuses on the police officers’ actions after the last shot, following which Nzoy collapsed on the ground. Through a combined analysis of video and audio evidence, police officers’ statements, police training manuals and a medical assessment, we demonstrate that after the shots, while Nzoy was clearly injured and in need of care, the officers did not share any relevant information about the situation and prioritised security handlings, such as a safety search and handcuffing Nzoy’s hands behind his back instead of offering first aid, which the officers were trained and required to provide. Our analysis further demonstrates that it is only after six minutes that a nurse, who was a witness to the scene, intervened spontaneously and was allowed to provide first aid.

Together, these combined steps in our analysis of the events lead us to fundamentally challenge the prevailing narrative according to which Nzoy constituted a threat to the officers that justified the use of lethal force. Our analysis further shows that Nzoy was not assisted in a life-threatening situation by the police officers, thus demonstrating a remarkable disregard for his life. Both the unfounded perception of Nzoy as a threat and the disregard for his life raise the question of how the perception of Nzoy as a “man of colour” – and thus the role of race – played in shaping the (in)actions of police officers, a question we respond to in Chapter 3.

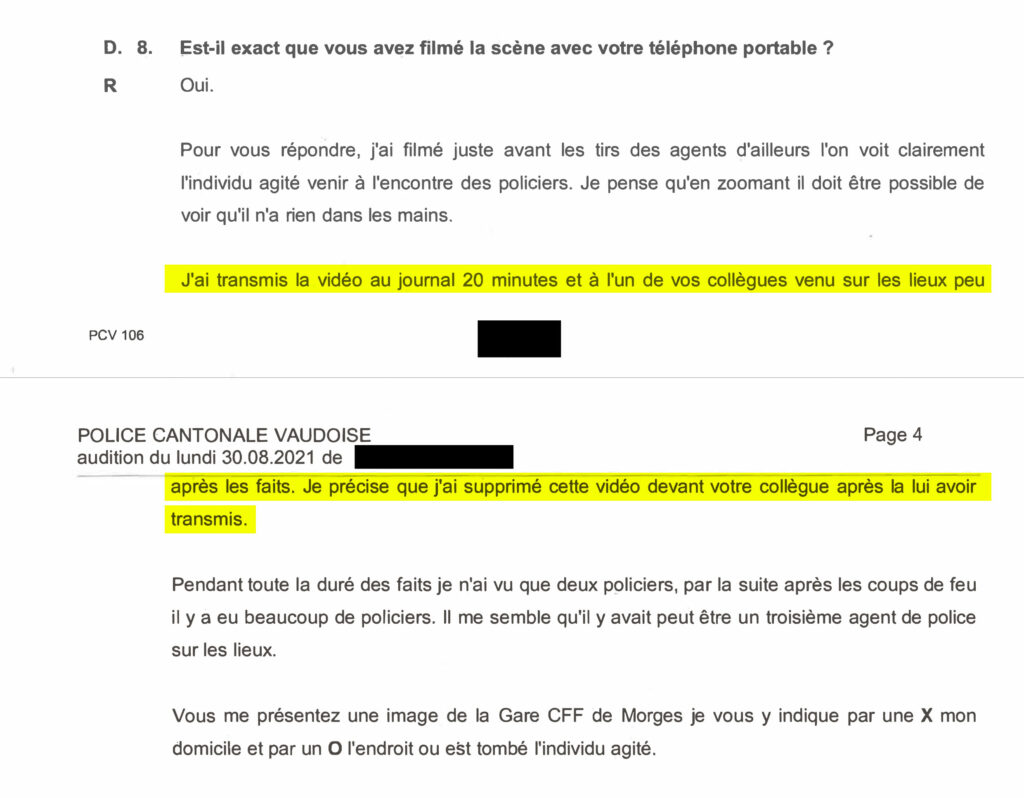

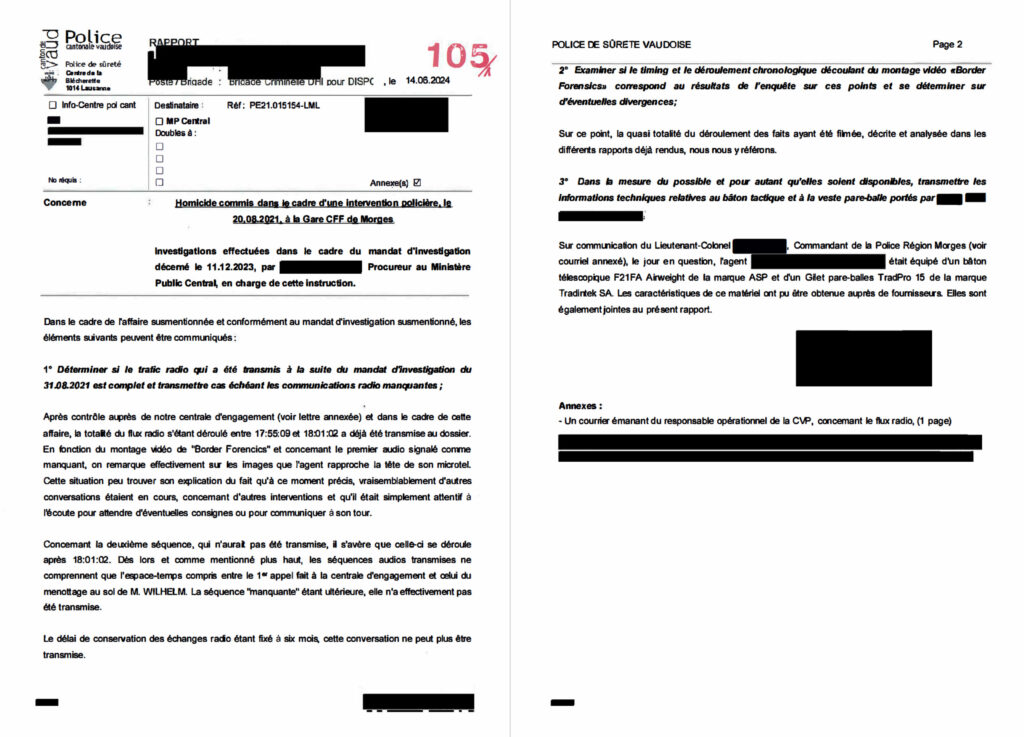

Chapter 2 continues our analysis at the level of the event, through the examination of the criminal investigation jointly led by the public prosecutor’s office of the Canton of Vaud and the Vaud Cantonal Police on the case. Our analysis of the case file reveals multiple deficiencies and evidentiary gaps of the criminal investigation, crystallising around the collection, processing and analysis of data. By cross-referencing video and audio data and analysing their metadata, we demonstrate that means of proof were altered, erasing their metadata and thereby critically hindering their use. We further uncover that radio communications are missing from the case file, leaving significant gaps in understanding the actions of the police officers and their potential consequences.

We finally cross-examine a police hearing transcript of one of the railway workers present at the station on that day (RW2) with videos and audio recordings of the events and reveal that his statements contain major inconsistencies that were not detected in the criminal investigation.

While Nzoy’s family and their lawyer, with the help of Border Forensics and the Independent Commission, repeatedly drew attention to these issues in the legal proceedings, the public prosecutor and the cantonal police systematically failed – or refused – to address them, constructing clear barriers to accountability. This not only hinders the quest for truth and justice in Nzoy’s case but also raises questions about the police and the public prosecutor’s will and capacity to effectively and transparently investigate a case of police-related death which we address in Chapter 4.

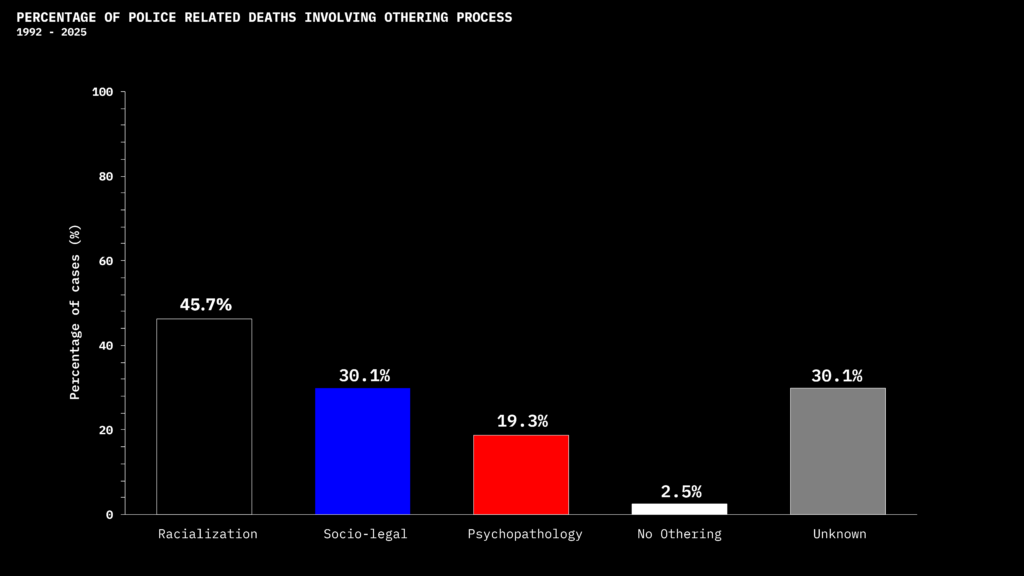

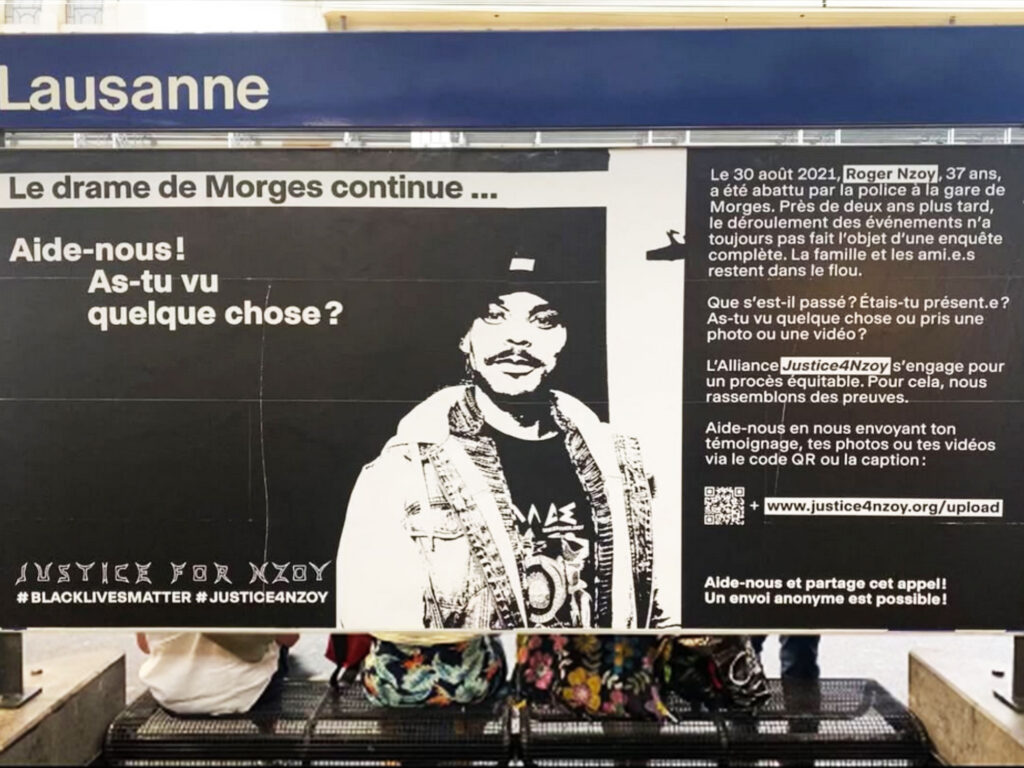

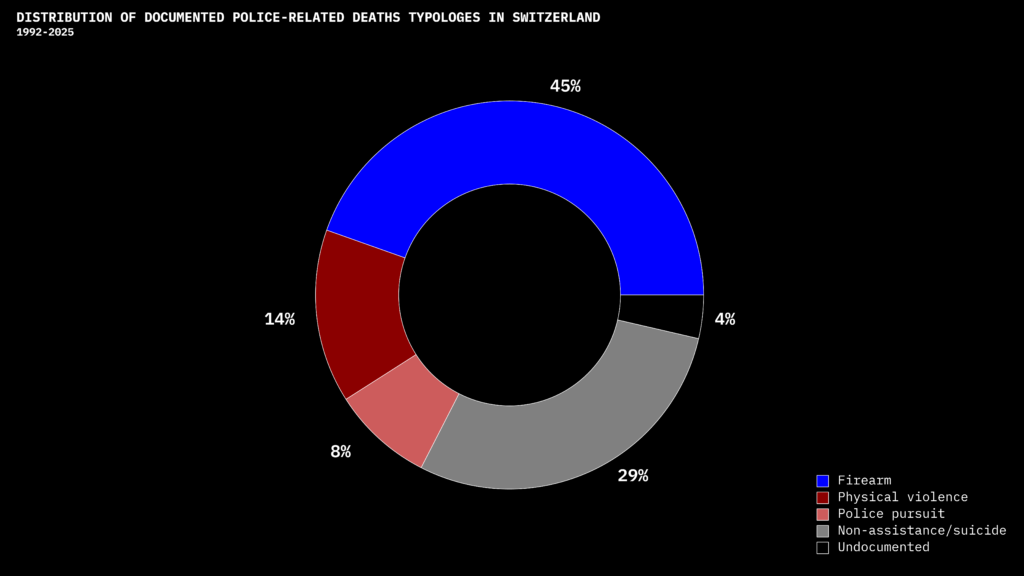

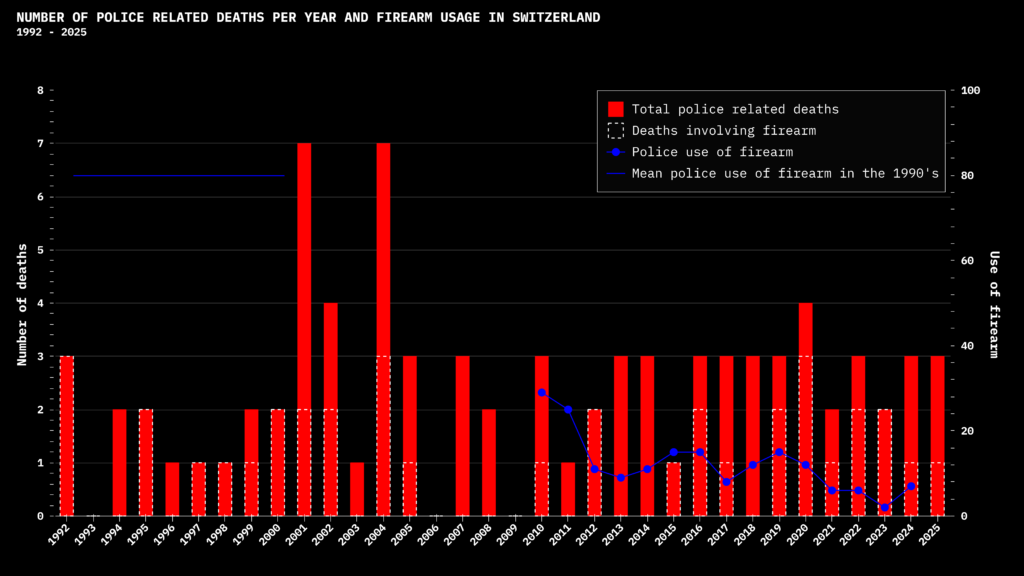

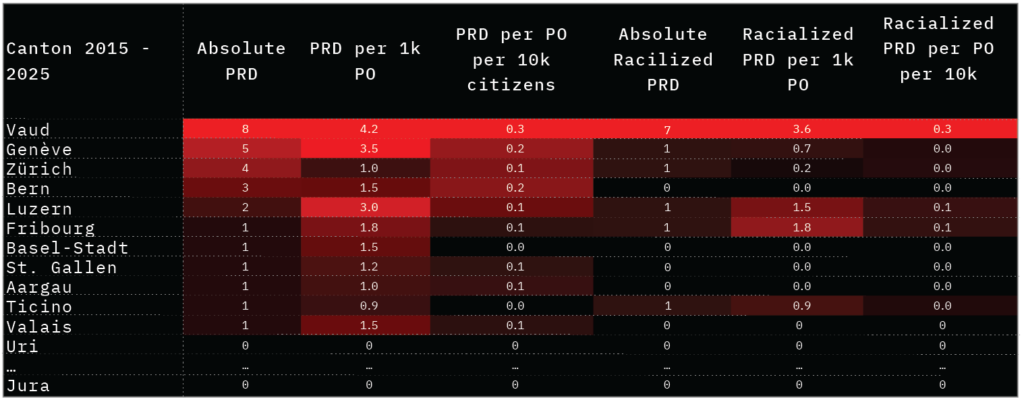

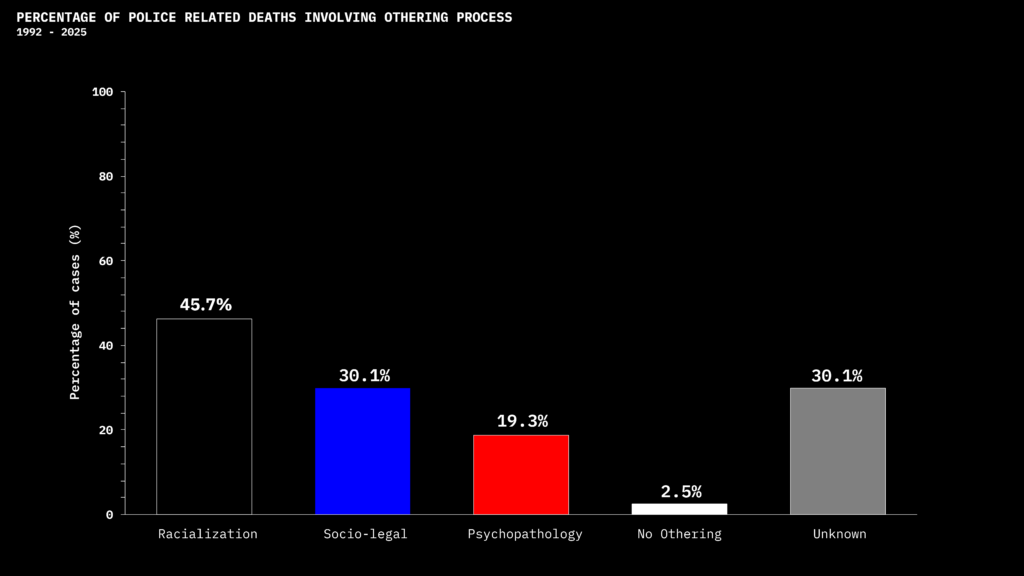

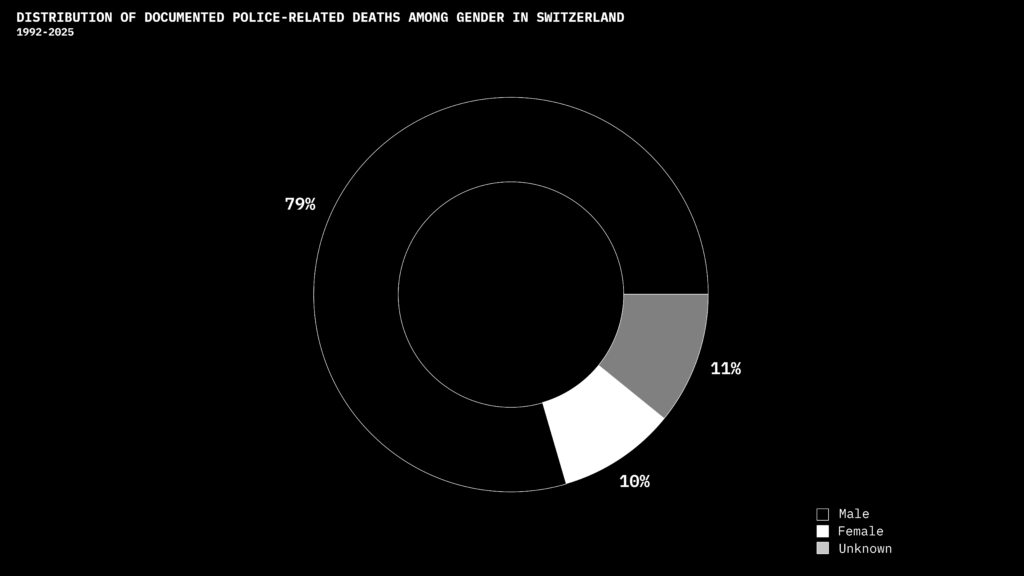

In Chapter 3, we seek to address the role of race in the killing of Nzoy. Towards this aim, and drawing on historical, institutional and statistical analyses, we analyse the structural conditions shaping police-related deaths in Switzerland. We first explore research conducted on the structuring role of race in Switzerland and the country’s occluded colonial history. We further analyse the way structural racism and denial operate in the practices of the Swiss police today. We then demonstrate that people – mostly men – perceived as others as a result of their racialisation, socio-legal status, psychopathology and drug use are disproportionately exposed to lethal police practices in Switzerland. To support this, and in response to the structural opacity of police institutions and the systematic lack of publicly available data on their activities, we have created a database of 83 cases of documented police-related deaths in Switzerland between 1992 and 2025 and compiled them into a cartographic platform – the Archive of Absence. This platform not only functions as a digital memorial for people who lost their lives at the hands of the police but also makes the othering processes people were subjected to legible.

An Archive of Absence: Dying at the hands of police in Switzerland. Interactive mapping platform to remember the deceased, acknowledge their absence and unveil the killings and their structure. Border Forensics, 2025The Archive of Absence

Headline figures from the Archive of Absence are unequivocal: at least 79% of documented police-related deaths were men. 67% of documented victims involve at least one axis of othering, and nearly a third (28%) involve more than one. More than 45% of the cases involved explicit or implicit racialisation processes; 30% concerned people with precarious socio-legal status; and almost 20% involved othering through psychopathology or drug-use. Together, these figures show that police lethality in Switzerland is not randomly distributed but structured by hierarchies of difference and disproportionately targets othered individuals.

On the day of his killing, Nzoy was described as a “man” and othered through his racialisation as a person “of colour” and perceived psychopathology. These intersectional and overlapping othering processes are identified by our analysis as particularly lethal in the Swiss context. Thus the combined othering that targeted Nzoy – compounded by masculinity – increased the risk of his exposure to lethal policing.

Our analysis also reveals that Nzoy’s geographical location in the Canton of Vaud on 30 August 2021 heightened this risk. According to our database, over the last decade, the highest number of documented police-related deaths in Switzerland occurred in the Canton of Vaud, with an over-representation of victims othered through racialisation. Brought together, the recent cases of police-related deaths in the Canton of Vaud express the tragic human toll of this pattern of police lethality: Hervé Bondembe Mandundu (Bex, 2016), Lamin Fatty (Lausanne, 2017), Mike Ben Peter (Lausanne, 2018), Nzoy (Morges, 2021), Qader B. (Essert-sous-Champvent, 2024), Michael Kenechukwu Ekemezie (Lausanne, 2025) and Camila Oliveira Belchior (Lausanne, 2025).

Combining our historical and statistical analyses of structural conditions shaping police-related deaths in this chapter with the findings of our previous chapters concerning the circumstances of Nzoy’s death and the processes of othering and the differential treatment he was subjected to, allows us to return to the question of the role of race in the unfolding of events. We conclude that it is highly probable that Nzoy’s killing was influenced by how he was perceived as a “man of colour” and a person affected by psychological disorder.

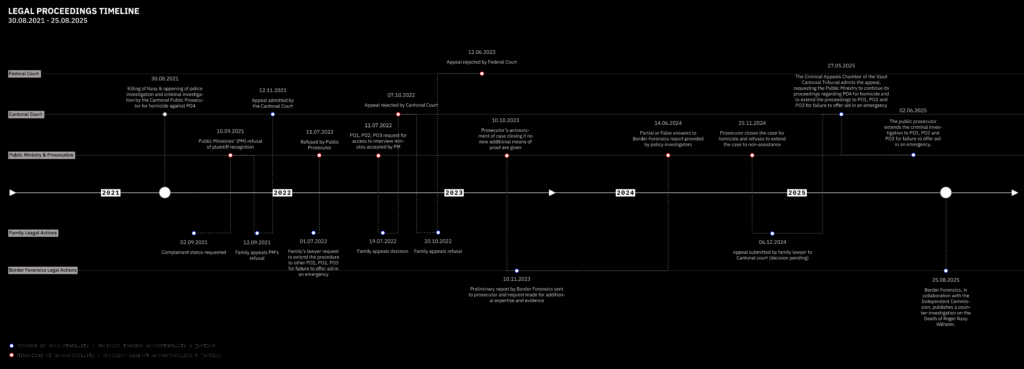

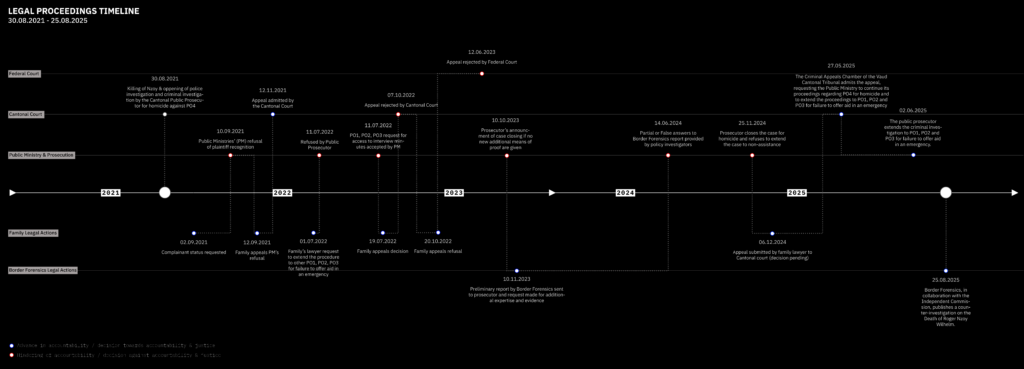

Chapter 4 addresses the structural conditions leading to the denial of truth and justice for victims of police-related violence and their families, with a specific focus on the Canton of Vaud. We analyse the structural entanglement between the police and the public prosecutor’s office in the conduct of criminal investigation in the Canton of Vaud, with a specific focus on the Special Police Investigations Unit (DISPO). Our analysis highlights the lack of independence in the conduct of criminal investigation, which has contributed to a lack of accountability in recent cases of police-related deaths. To date, all documented cases over the last ten years remain under prolonged criminal investigations, or are pending in Swiss or international courts after families have challenged verdicts ruled against them. As a result of these repeated barriers to accountability, justice appears elusive and forever deferred for victims’ families.

We further analyse the barriers to justice experienced by families and the perpetuation of violence through the legal process, with a specific focus on Nzoy’s case. We discuss particular barriers to accountability and the violence that families experience through the negative portrayal of their loved ones in the legal process, which is further amplified by the media. These portrayals shift the focus away from the police-related death to the alleged faults or threats of victims. Such portrayals both legitimise the actions of police officers and further stigmatise the families, who are forced to watch their loved ones represented in legal proceedings in ways that are unrecognisable to them. In these instances, it is the memory of a loved one that is violated, after the person themself has already been killed.

Together, our analysis demonstrates that the legal institutions of the Canton of Vaud charged with determining responsibilities in cases of police-related violence are far from offering an adequate response to the demands for accountability. The legal process comes at a tremendous cost for the families, while the officers implicated in police-related deaths are very rarely condemned for their (in)actions. Furthermore, racism itself is not addressed in these legal processes and remains unchallenged. Structural impunity thus operates across a continuum which in turn enables the perpetuation of police violence onto future victims. The acknowledgement of the limits of the law and the violence of the legal process itself has spurred anti-racist movements to consider alternative justice-seeking practices both within and without the institutions of the law.

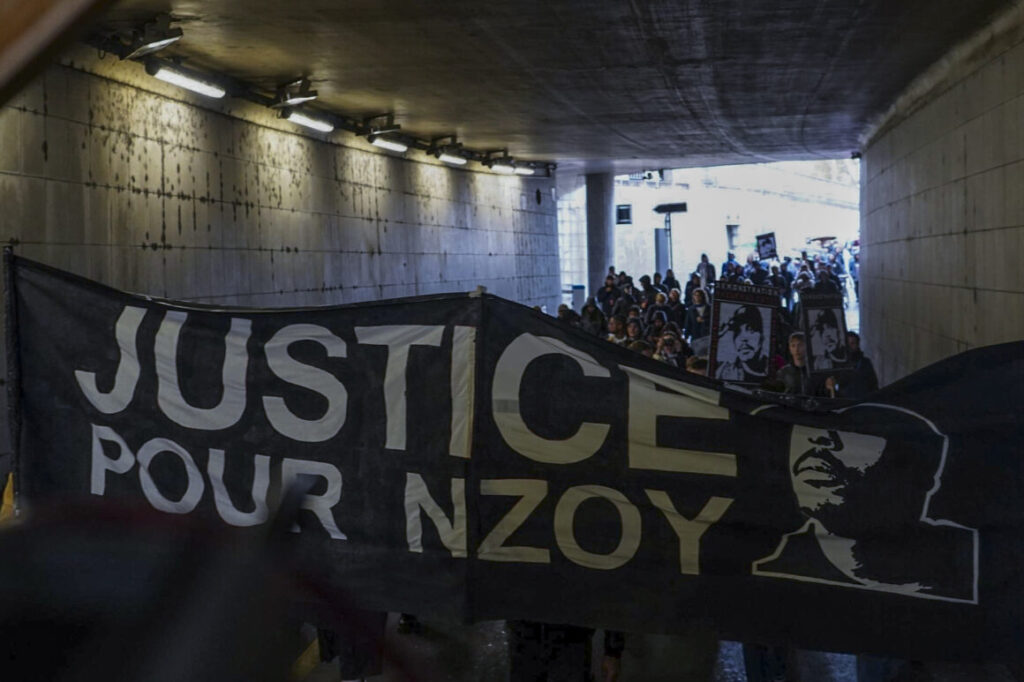

The Conclusion brings together the two analytical levels of this report and reflects on the meaning of “Justice for Nzoy” – the demand that has been voiced by his family and which resonates throughout demonstrations. It is understood at once as a call to uncover and disseminate the truth about his death, to pursue accountability through legal forums despite their systemic limitations,to rethink justice beyond punitive state institutions and to restore Nzoy’s memory. We specifically address the ways in which this counter-investigation has answered this call. Grounded in the Nzoy case but against a backdrop of other police-related deaths in Switzerland, our results are summarised. At the same time, they highlight how Nzoy’s family, together with activists and collectives, has forged alternative practices of justice rooted in solidarity, truth-telling and collective memory, sustaining both resistance and care while envisioning systemic change.

In summary, our counter-investigation reveals the killing of Nzoy in a fundamentally new different light. We demonstrate that:

- Nzoy was not attacking PO4 and that it is highly likely that he did not have a knife in his hands before the first two shots were fired. Based on an inaccurate and biased perception of threat, the police officers wrongfully privileged the use of coercitive means and lethal force against Nzoy instead of assistance and care. This led to the escalation of the situation resulting in the fatal shooting of a person in a state of psychological distress.

- The police officers did not provide aid to Nzoy, who was in urgent need of assistance after being shot, and prioritised security measures despite the absence of threat. An off-duty nurse witnessing the events presented himself on the scene four minutes and 40 seconds after the last shot and conducted first-aid measures six minutes after the last shot, followed by the intervention of emergency services.

- The perception of Nzoy as a “man of colour” likely shaped the events that led to his death. The specific circumstances of his death indeed correspond to a clear pattern of relation between processes of othering and overexposure to the risk of police-related death which emerges from our statistical analysis.

- The cantonal police and the public prosecutor failed to conduct a detailed, fact-based and impartial investigation on this case. The criminal investigation contains several inaccuracies, and crucial means of proof have been altered or are missing from the case file. Analysing the legal and procedural functioning of this and other similar investigations, our report interrogates the capacity and willingness of state institutions to conduct an independent and impartial process that guarantees accountability.

- The violence experienced by Nzoy, and by extension his family and close ones, did not end with the fatal shooting but continued throughout the legal proceedings, and was particularly intensified by the victim–perpetrator reversal propagated in the public sphere by the police, the public prosecutor and some media outlets.

It is our hope that this counter-investigation may support Nzoy’s family’s quest for truth and justice. While this investigation primarily focuses on reconstructing the specific circumstances and conditions that led to the killing of Nzoy, we do not wish to reduce him to his death. We thus conclude this summary with the words of Nzoy’s sister, which bring to life the memory of who he was:

“I want the world to remember him as he was – a cheerful, funny, helpful being, a human. I really want his laughter and his helpfulness to be remembered, his humanity, his compassion, his empathy for people, his love for people. That is what I would like to keep in memory of him. And of course his laugh, and his hugs, and his dimples, and his curls… There’s actually so much; a whole list of things one can remember about him.” – Nzoy’s sister

Investigation methodology

While we define our specific methods, techniques and tools in each chapter, in this section we outline our overall investigation methodology – the framework in which our research is conducted with particular attention to our counter-forensics practice in relation to racist violence and the ethical considerations that guide our work.

A collaborative counter-forensics practice

Border Forensics is a research and investigation agency founded in 2021 and based in Geneva. Border Forensics’ work is anchored in a counter-forensics practice that critically mobilises methods of spatial and visual analysis to investigate violence, in particular related to the existence and management of borders. Border Forensics strives to combine in a mutually reinforcing way cutting-edge and rigorous methodologies towards evidence-based analysis, critical and reflexive thinking and creative aesthetic practice. While we often harness data and methods used by states towards surveillance, we mobilise them critically in the aim of revealing the practices and actors responsible for violence and human rights violations while not exposing the dignity of those whose lives have been violated.

Our previous investigations to date have focused on the continuum of border violence that affects the entire trajectories of migrants from the global south. We have paid particular attention to the ways in which the policing of borders and of the boundaries of race intersect, showing that racial categorisation crucially influences who border agents target and the use of excessive violence against them. With this investigation, we focus on the policing of the boundary of race as such. The boundaries of race, just like state borders, result in the assignation of people to their differences, hierarchisations in human dignity and rights, and ultimately differential treatment and exposure to violence.

Throughout our investigations, we work in direct collaboration with affected communities, non-governmental organisations as well as other civil society groups to support their demands for truth and justice. For this investigation, we have collaborated with Nzoy’s family and with the Independent Commission. Formed in 2023 on the models of international commissions that independently examine police behaviour and investigate cases of police-related deaths, it is composed of lawyers, psychologists, physicians, sociologists, political scientists, anthropologists, historians and cultural scientists who have worked closely with Nzoy’s family and their lawyer. Border Forensics and the Independent Commission’s analyses are combined to construct an empirical and fact-based investigation.

The challenges of critically investigating racist violence

As Eyal Weizman, one of the founders of the critical forensic practice our methodology engages with, describes in a co-authored text, a key characteristics of critical forensic practice is that it strives to address both minimal causation, “the minimal act, or inaction, that causes a crime to occur”, and field causality: “The complex multiple causes, which may be social, cultural, economic, environmental, and so on, that bear on a particular event.”8Matthew Fuller and Eyal Weizman, Investigative Aesthetics: Conflicts and Commons in the Politics of Truth (Verso Books, 2021), 137–38. This methodological orientation is all the more important when focusing on forms of violence involving racial categorisation, and specifically anti-Black violence.

Scholars of Black studies emphasise that “Black death is not an event, but a continuum that intimately informs Black existence”.9Norman Ajari, “Forms of Death: Necropolitics, Mourning, and Black Dignity,” Symposium: Canadian Journal of Continental Philosophy 26, no. 1/2 (2022): 175, https://doi.org/10.5840/symposium2022261/29. Although cases of violence targeting Black people can be spectacularly revealed during specific events – such as the killing of Nzoy – the violence that permeates the daily lives of Black people is often far less sensational and documented. Yet this everyday violence – often invisible and unrecognised – is essential to take into account. If, as the philosopher Norman Ajari notes, “the way in which a Black person dies in a racist world is in continuity with the way in which he is bound to live in it”,10Norman Ajari, La Dignité Ou La Mort: Éthique et Politique de La Race, Les Empêcheurs de Penser En Rond (La Découverte, 2019), 100. then when investigating incidents that target Black people, the frame of analysis must be extended beyond the space-time of the event of their killing, so that the structural conditions that have enabled many similar violent events to occur can be addressed. These considerations, in which critical forensic practice and Black studies methodologically converge, have been key in shaping the two analytical levels that we have used to structure our inquiry – the event and the structural conditions. While in Chapters 1 and 2 we have primarily mobilised spatial and visual investigative methods to reconstruct meticulously the unfolding of events on the day of the killing of Nzoy, in Chapters 3 and 4 we extend our investigation beyond “the cordoned-off area of the crime scene”11Fuller and Weizman, Investigative Aesthetics: Conflicts and Commons in the Politics of Truth, 137. and use historical, legal and statistical analysis to account for the broader structural context of racism and impunity that made his killing possible.

The analysis of racist violence also raises other ethical and political challenges relating to the use of the images and other evidence documenting the violence. While reconstructing events and making visible violent practices are crucial for contesting them and seeking truth and justice, it is also necessary to consider how these documentation strategies might inadvertently reproduce dehumanisation and harm for those affected. We believe two issues in particular demand critical reflection and experimentation. First, Black studies and feminist scholars have shown that the hoped-for and assumed effects of disseminating images of violence – that their visibility would lead to at least public, if not legal, condemnation, and ultimately to the cessation of the violence – are often not realised when the targets of the violence are Black people. On the contrary, the dissemination of images of violence against Black people contributes to its normalisation and thus to its perpetuation.12Christina Sharpe, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (Duke University Press, 2016), 116–17. Second, this important history of research and political engagement on racism and policing has indeed critically addressed the ethics and politics of representation of violence against Black bodies. As put forward by author and activist William C. Anderson: “Dead Black people are not ornaments to be put up and taken down for every activist need, purpose and point. […] We run the risk of reducing them to just a death and erasing the beautiful existence many of them had prior to the deadly moments that introduced them to us all.”13William C. Anderson, “From Lynching Photos to Michael Brown’s Body: Commodifying Black Death,” Truthout, January 16, 2015, https://truthout.org/articles/from-lynching-photos-to-michael-brown-s-body-commodifying-black-death/.

In investigating and documenting Nzoy’s death, we face an ethical imperative: to make the violence he suffered visible and intelligible without reproducing its conditions of dehumanisation and normalisation. To do so, we seek to exercise the “disobedient gaze” that Border Forensics has developed in the course of its investigations, through which we attempt to make visible the violence and the responsibility of states, while protecting the identity and dignity of those whose lives and rights have been violated.14Charles Heller and Lorenzo Pezzani, “A disobedient gaze: strategic interventions in the knowledge(s) of maritime borders.” Postcolonial Studies 16(3), 2013, pp. 289-98. We further follow Black feminist scholars and activists in the aim of adopting an approach that prioritises relationality, care and the dignity of the victim, casting a non-voyeuristic and an anti-racist gaze upon them, while consciously rejecting the extractive and spectacularising tendencies of forensic or carceral forms of knowledge production. We further embrace what Édouard Glissant calls the “right to opacity”,15Édouard Glissant, Poétique de la relation (Gallimard, 2012), 203–10. which asserts that individuals – particularly those who have been historically objectified by the colonial gaze – are not required to make themselves fully visible, legible or understandable to those in power. Opacity is not about obscuring the truth; it is about safeguarding the personhood and dignity of the victim, recognising the entirety of a person’s life beyond the moment of their violation, and not reducing them to their death.

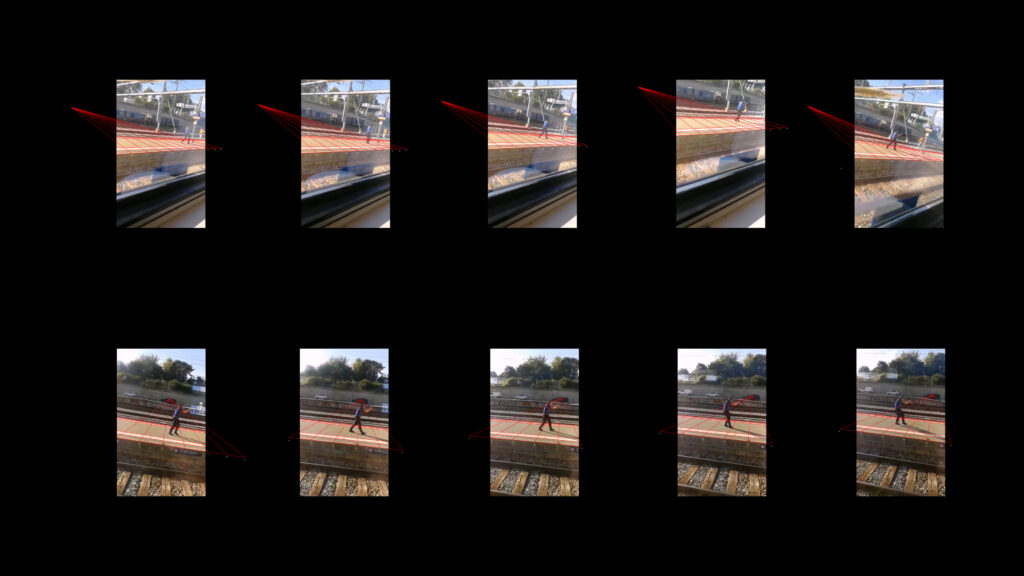

We use this ethical approach as a compass to prioritise re-humanisation rather than brutalisation and criminalisation. Remaining in constant dialogue with Nzoy’s family and close ones, we have discussed what can and should be presented in the investigation and how. Their perspectives have shaped both the form and the content of this work. When discussing the video images of Nzoy’s killing with Nzoy’s sister, she told us: “I don’t want to see him dying over and over again.” She further expressed the desire to protect Nzoy’s dignity, in particular not to publicly show video sequences depicting Nzoy being shot or lying on the ground. To respond to her demands without losing the evidentiary value of this video material, we have drawn inspiration from the strategies of Black studies scholars and Black artists who have mobilised “redaction” as a critical practice.16Sharpe, In the Wake. While redaction is often used by states to shield state actors from public scrutiny, redaction can also be mobilised by non-state actors to protect the identities and dignity of subaltern subjects. Here, in Nzoy’s sister’s proposition, redaction operates as a visual cover, which protects and gives privacy to her deceased brother.17All videos we mobilise in our reconstruction are included in the case file and are thus available unredacted to all actors involved in the legal proceedings. As well as a refusal of the state’s reduction of Nzoy’s life to a case file, this is a visual gesture of care and an affirmation of his humanity, his personhood and his enduring presence in the lives of those who loved him.

CHAPTER 1. FROM DISTRESS TO DEATH: RECONSTRUCTING THE KILLING OF NZOY

Nzoy died on 30 August 2021 at Morges train station after being shot three times by a Morges police officer (PO4) and left unassisted for six minutes. Four years after the event, and after two failed attempts from the public prosecutor to abandon the proceedings, the criminal investigation has not yet shed light on the circumstances that led to Nzoy’s death. Until now, the criminal investigation has constructed a simple and seemingly straightforward depiction of events based on incomplete or false accounts, leading to erroneous conclusions that ultimately criminalise Nzoy and legitimise his killing.

By cross-referencing all the evidence of the case file and new evidence we generated in the course of our investigation, our analysis provides a detailed understanding of the unfolding of events, summarised in a cartographic and videographic reconstruction. At the request of Nzoy’s family, and for reasons described in our methodology, in the aim of protecting Nzoy’s dignity we have redacted all video sequences showing Nzoy being shot or dying on the ground.

Throughout this report we demonstrate that the actions of the police officers, and their inaccurate perception of Nzoy as a threat, rapidly led to the use of coercitive means and the subsequent prioritisation of security measures instead of assistance and first aid, clearly neglecting Nzoy’s health and wellbeing. In this chapter, we analyse the circumstances and (in)actions of the four police officers involved (PO1, PO2, PO3, PO4) that led to Nzoy’s death on 30 August 2021, while presenting in detail the sources we used and the methods we developed.

Before offering our evidence-based reconstruction of events, we discuss the conclusions of the criminal investigation that gives an account of the events that our reconstruction and analysis contradict.

The criminal investigation and the construction of an erroneous narrative

In the direct aftermath of the shooting of Nzoy, we understand from the record of operations contained in the case file that the forensic police is mobilised on the scene. While the exact chronology of the actions is unclear, a bigger dispositif seems to be put together later on, coordinated by an on-duty prosecutor, with medical forensic doctors conducting an analysis of Nzoy’s body and later an autopsy, as well as cantonal police inspectors gathering means of proof and conducting police hearings with the four police officers involved as well as witnesses.

At around 18:25, the case file indicates that the following information is shared with the on-duty prosecutor:

“On this day, at around 17:55, the Operations Center was notified of gunshots fired by the police at Morges railway station. In substance, the first elements indicate that [Morges Regional Police] officers were dispatched for a disturbed individual at Morges station. Upon arrival, the aforementioned man, armed with a knife, moved towards them in a threatening manner. Three gunshots were then fired by the police. The individual is currently believed to be injured, placed in the recovery position, and handcuffed. The crime scene has been secured; the [Forensic Police Brigade] is on site.18“Ce jour, vers 17h55, la Centrale d’engagement a été avertie de coups de feu tirés par la police en gare de Morges. En substance, il ressort des premiers éléments que des agents de la PRM ont été engagés pour un individu perturbé en gare de Morges. Lorsque les policiers sont arrivés sur place, l’homme précité, muni d’un couteau, s’est dirigé vers eux de manière menaçante. Trois coups de feu ont alors été tirés par la police. Actuellement, l’individu serait blessé, placé en position latérale de sécurité et menotté. La scène de crime a été figée ; la BPS se trouve sur les lieux.” Case file, 3015, p.2

While this depiction of events was put forward before Nzoy’s death was pronounced, it continues to be used as a dominant narrative in the criminal investigation four years after he died. A criminal investigation for homicide was opened the next day against PO4 by a public prosecutor of the Canton of Vaud attached to the Special Police Investigations Unit (DISPO).19In Switzerland, cantonal public prosecutors oversee criminal investigations and prosecutions under the Swiss Code of Criminal Procedure and Cantonal laws. They conduct preliminary proceedings, collect evidence, coordinate and instruct police investigations and, if necessary, represent the prosecution in cantonal and federal courts. The role of the prosecutor in a criminal investigation is thus prominent and its tasks and power are vast. In 2020, the Public Prosecutor’s Office of the Canton of Vaud and the Vaud Cantonal Police established the Special Police Investigations Unit (DISPO). Defined as a unit tasked with handling criminal investigations related to police activities and penitentiary matters, it is composed of public prosecutors and police officers from the Vaud cantonal police. As for other cases of violence and deaths involving police officers on duty in the Canton of Vaud, the DISPO is in charge of the criminal investigation into the death of Nzoy. We further discuss issues related to the DISPO and the structural conditions in which it participates in Chapter 3. The public prosecutor also issued a formal investigation mandate assigned to a cantonal police inspector attached to the DISPO.

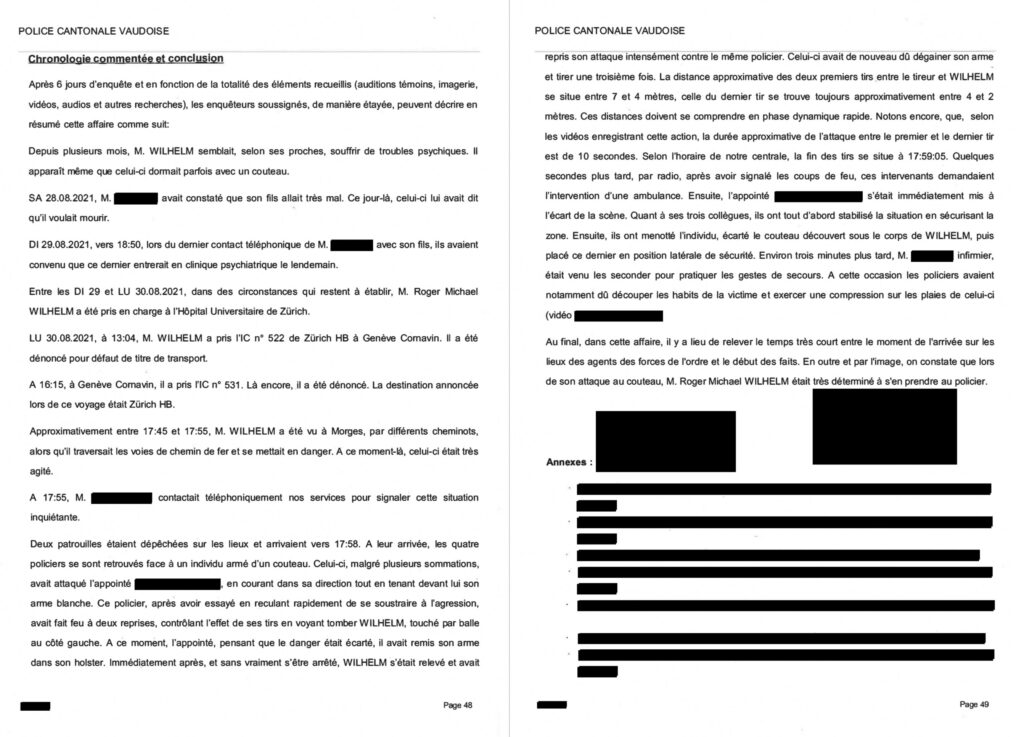

On 6 September 2021, based on transcripts of police hearings, imagery, videos, radio communication recordings and the preliminary medical forensic report, the cantonal police inspectors submitted their conclusions to the criminal investigation. Their conclusions, which we discuss and oppose in this chapter, state that on 30 August 2021, Nzoy – having shown signs of psychological distress for several months – was seen “highly agitated” and crossing train tracks at Morges station. The conclusions further state that when two police patrols arrived, alerted by a railway worker, they faced an individual “armed with a knife”. Ignoring police officers’ orders to drop the knife, Nzoy allegedly ran towards PO4 “holding his knife in front of him”, and was shot twice. He fell, then rose and “resumed his attack intensely against him”, prompting a third and last shot. Police investigators further state that medical assistance was called and that PO1, PO2 and PO3 first stabilised the situation by securing the scene then handcuffed Nzoy, removed the knife found under him and “placed him in a lateral safety position”, after which a nurse arrived to “assist them to administer first aid”. The conclusions finally emphasise the rapid progression of events and the fact that Nzoy was “very determined to attack the police officer” during “his knife attack”.20Case file, 4001, p.48–49.

The conclusions of the police investigation reproduce the initial narrative constructed in the direct aftermath of the shooting, and was sealed seven months later by an analysis conducted by a cantonal police officer of the police training unit,21Case file, 4014 whose impartiality and independence have been later contested.22Arrêt Du 14 Mai 2025, PE21.015154-LML (2025). https://www.findinfo-tc.vd.ch/justice/findinfo-pub/internet/search/result.jsp?path=10348518&title=D%C3%A9cision%20/%202025%20/%20254&dossier.id=10277078&lines=10.

While this police investigation was ongoing, local media published eyewitness videos of the events showing that police officers actually did not conduct first aid, which started to raise questions about their possible failure to offer aid. Activist groups also rapidly organised to denounce Nzoy’s killing, problematise its racist character and call for truth and justice on a highly opaque unfolding of events.23Pauline Rumpf, “Il est resté couché bien cinq minutes, menotté, avant d’être secouru,” 20 minutes, August 31, 2021, https://www.20min.ch/fr/story/il-est-reste-couche-bien-cinq-minutes-menotte-avant-detre-secouru-336314064179; Renversé.co, “Morges : Rassemblement Contre Les Crimes Policiers,” September 2, 2021, https://renverse.co/infos-locales/article/morges-rassemblement-contre-les-crimes-policiers-3204.

After two years punctuated by legal actions from Nzoy’s family demanding to extend the case to PO1, PO2 and PO3 for failure to provide aid in an emergency, by requests for independent expertise and by legal disputes concerning police officers’ access to transcripts of hearings, the public prosecutor considered the criminal investigation complete. He announced his will to issue an abandonment of the proceedings for homicide against PO4 and a no-proceedings order for failure to offer aid in an emergency for PO1, PO2, PO3 and PO4.24RTS, “Le procureur veut classer l’enquête contre le policier qui a tué Nzoy,” November 10, 2023, https://www.rts.ch/info/regions/vaud/14459300-le-procureur-veut-classer-lenquete-contre-le-policier-qui-a-tue-nzoy.html.

In response, Border Forensics produced a preliminary analysis in collaboration with the Independent Commission in November 2023 preventing the abandonment and the no-proceedings order. Our analysis demonstrated that the police officers indeed failed to offer aid to Nzoy after the shooting, prioritising security measures instead, even though he did not pose any threat. We further revealed that police radio communications are missing from the case file.25Border Forensics, “Joint Statement and Release of a Preliminary Analysis on the Death of Roger ‘Nzoy’ Wilhelm,” November 10, 2023, https://www.borderforensics.org/news/20231110-pr-roger-nzoy-wilhelm/.

A year after our preliminary report was added to the case file, without presenting contradictory information or addressing the missing evidence, the public prosecutor effectively issued an abandonment of the proceedings for homicide and a no-proceedings order, arguing that PO4 shot in self-defence and that the failure to offer aid in an emergency could not be held against him or his three colleagues.26Ministère Public, “Homicide à la gare de Morges : le Ministère public retient la légitime défense et écarte l’omission de porter secours,” November 26, 2024, https://www.vd.ch/actualites/communiques-de-presse-de-letat-de-vaud/detail/communique/homicide-a-la-gare-de-morges-le-ministere-public-retient-la-legitime-defense-et-ecarte-lomission-de-porter-secours. The family’s lawyer appealed this decision and the Criminal Appeals Chamber of the Vaud Cantonal Tribunal cancelled the no-proceedings order, instructing the public prosecutor to continue the criminal investigation and to open a proceeding against PO1, PO2 and PO3 for failure to offer aid in an emergency.27Arrêt Du 14 Mai 2025, PE21.015154-LML, https://www.findinfo-tc.vd.ch/justice/findinfo-pub/internet/search/result.jsp?path=10348518&title=D%C3%A9cision%20/%202025%20/%20254&dossier.id=10277078&lines=10

Over the four years since Nzoy’s death, the narrative that PO4 shot Nzoy in self-defence after being attacked with a knife has dominated the criminal investigation as well as the public understanding of the case, reinforced by reports and analyses conducted by employees of the cantonal police. Our counter-investigation provides for the first time a detailed and fact-based analysis of events and refutes the conclusions of the criminal investigation outlined above. While we address in detail the deficiencies of the criminal investigation in the subsequent chapter, our analysis shows that it presents a simplified unfolding of events, a misleading interpretation of the threat and unreasonable speculation about the presence of a knife at crucial moments before the shooting.

Border Forensics’ reconstruction process, sources and methods

Our investigation draws on a wide range of material that necessitates a careful and transparent examination, combining data from the case file and evidence gathered or produced by Border Forensics or the Independent Commission. This multi-source approach not only allows for a precise reconstruction of events but also makes it possible to fill the gap when material is altered, omitted or missing in the criminal investigation and the case file. Here, we detail our reconstruction process and discuss the sources we use.

For the purpose of this investigation, Nzoy’s family gave us access to the case file compiled in the context of the criminal investigation coordinated by the public prosecutor’s office of the Canton of Vaud. We systematically examine the data it contains critically before use, organising and cross-referencing them with multiple sources or additional analysis to assess their accuracy and relevance to the investigation. We give particular attention to the ways in which the data of the case file was constructed, collected, shared, concealed and used in the criminal investigation. When confronted with inaccurate, incomplete or nonexistent accounts of certain events or actions, we use and develop visual and spatial analysis methods – such as video-pixel analysis and 3D reconstruction – that allow us to bridge the gaps between the known and the unknown. Our methods are described transparently and the level of certainty of our results and the accuracy of the data used is systematically indicated through in-text mentions and visual interventions.

Border Forensics and the Independent Commission have also gathered and produced different data and evidence. Faced with some gaps in the case file that we address later in this report, the Independent Commission and the activist alliance Justice4Nzoy organised a public call to recover information on the event. This action allowed us to gather testimony and a new video of the event captured by an eyewitness. This type of publicly-collected data undergoes the same cross-referenced verification process and is used in our reconstruction of events.

Finally, the Independent Commission has also produced targeted and contextual expert reports. These include: a psychiatric assessment of Nzoy’s behaviour, a medical assessment of Nzoy before and after the shooting, legal analyses of the criminal investigation and the ongoing legal process, historical analyses of Swiss colonial history and racism, media analysis of the case’s coverage, analysis of political debates and decisions on policing, and reflections on justice and its alternative forms. Supported by empirical and theoretical research, the expertises the Independent Commission has assembled are crucial to this counter-investigation and are integrated in this report.

Sources included in the case file

The data available in the case file have been collected by a variety of actors – mostly employees of the cantonal police – involved at different steps of the criminal investigation coordinated by the public prosecutor in charge. As of this publication, the case file includes:

- 23 transcripts of police hearings conducted with 11 witnesses, the four police officers involved (two hearings each), two forensic doctors, one police captain, the nurse who intervened to provide first aid and Nzoy’s father (internal ID system: 2000)

As no audio recordings of police hearings are present in the case file, the transcripts constitute reported statements written by police officers. Although in Switzerland police officers have the legal obligation to let the person interviewed review the hearing transcript before signing it,28“Swiss Criminal Procedure Code,” https://www.fedlex.admin.ch/eli/cc/2010/267/en, art. 78. statements in the transcripts cannot be taken as verbatims. Furthermore, as it is common in multiple recollections of the same event, testimonies usually diverge about its unfolding and its interpretation. The period between the events and the hearings also allowed for the circulation of public discourse, video footage, media articles and internal police reports, which may have shaped – explicitly or implicitly – the officers’ retrospective framing. The four police officers, who remained on active duty in the Morges police and continued working together, had opportunities to discuss the events, raising the possibility that convergences in their accounts may reflect not coincidence but conscious or unconscious harmonisation. Whenever statements from police hearings are used, they thus undergo careful examination through documented cross-referencing with other sources to assess their relevance and veracity.

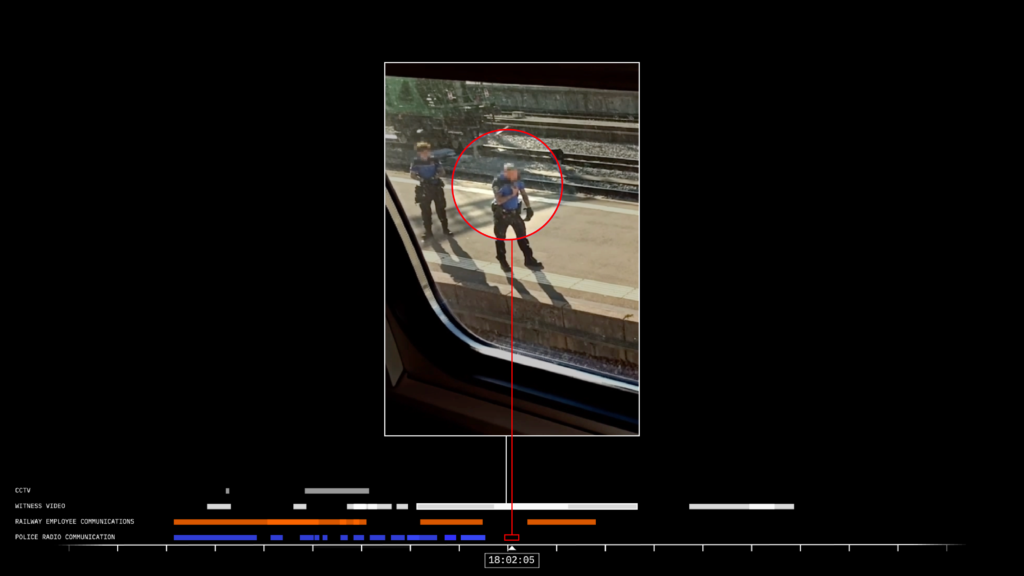

- 15 videos recorded by witnesses or transmitted by Swiss Federal Railways and 15 photographs taken by witnesses (internal ID system: 1000)

As the incident took place during a weekday rush hour in a train station, while a train was held at a platform close to the violent encounter between Nzoy and the police officers, an important number of videos and photographs of the events were captured by eyewitnesses at different moments of their unfolding. These videos and photographs were gathered on the evening of the incident as well as during the following days on site and during police hearings. There were no surveillance cameras installed on the station platform. Some images, however, were obtained from the ticket machine at the station entrance and from cameras mounted inside the train stopped next to the scene. These videos were selected and transmitted to the police. It remains unknown whether other ticket machines or train-mounted cameras recorded the scene, but it appears that no fixed platform cameras existed at the time. We analyse their content and their metadata – the data recorded in a file that provides such information as the date, time and location of the file creation, as well as characteristics of the device used to create the file (e.g. camera model). This allows us to assess whether data shows signs of alteration or modification – something that we address in detail in Chapter 2 – and evaluate their relevance to our analysis.

- 13 audio recordings of police radio communication of varying length and one audio message from a witness (internal ID system: 1000)

Police radio communications were obtained from the police dispatch center – known at the time as the CET – and subsequently added to the file. All audio recordings were carefully examined to identify speakers, and were cross-referenced with visual material to assist in speaker identification and to detect missing information that was – intentionally or otherwise – not provided in the case file. The witness’ audio message contains no relevant information and is therefore not used in the investigation.

- Three abstracts of police training manuals (internal ID system: 7000)

Those elements consist of a selection of official Swiss police training manuals focusing on police shooting, tactical first aid and personal security. They are used in our analysis of the four sequences of events to understand and assess the police officers’ actions.

- One police investigation report, one forensic police investigation report, one police report on the “professional acts” of the police officers, one preliminary forensic medical report and one final forensic medical report (internal ID system: 4000, 8000, 5000)

These reports produce evidence and analysis on the unfolding of events that we systematically verify before using, while demonstrating some of their methodological and evidentiary limitations. They also contain substantial visual data as well as documents produced or obtained in the course of these investigations.

- Several letters and documents pertaining to the legal procedure and the criminal investigations (internal ID system: 3000, 6000, 7000)

These elements are used to understand and contextualise the unfolding of events as well as the criminal investigation processes and the legal issues that they raise.

Border Forensics’ reconstruction of the events

Our reconstruction divides the unfolding of events into four sequences corresponding to key stages of the events, which we analyse chronologically.

The first sequence we analyse focuses on the situation at Morges station before the arrival of the first and second police patrols. During this period, Nzoy exhibited behaviour indicative of a plausible psychological disorder, with indications pointing towards a psychotic episode. This is a temporary mental state in which a person loses the ability to correctly perceive or interpret reality, often involving delusions or hallucinations. The interaction with railway workers shows Nzoy attempted to maintain distance and expressed a desire to be left alone, highlighting his vulnerability rather than hostility.

We constructed an animated cartographic and videographic reconstruction by plotting the positions of all actors across the period of the first sequence on a georeferenced plan of the station platform. Sources used were the transcripts of police hearings, videos and audio recordings, which we synchronised into a single timeline. We also visualised the movements of the actors, incorporating uncertainty encoding. Radio communications used here are a selection provided in the case file; we later document missing radio communications and assess their implications. Because many files arrived re-encoded (e.g. via WhatsApp) with altered or missing metadata, we restored ordering through audiovisual matching. When video or audio coverage was absent, we triangulated positions and actions from police and witness hearings, critically weighting statements and documenting confidence levels.

The second sequence focuses on the arrival of the first and second patrols and the triggering effect it had on Nzoy, leading to a rapid escalation of the situation. Upon arrival of the patrols, Nzoy’s state shifted significantly; he became visibly more agitated, panicked and fearful. The intervention of the second patrol, arriving spontaneously, without clear necessity and rushing, heightened the stress and confusion for Nzoy, causing his behaviour to change from withdrawal to panic. This reaction can be attributed to his psychological distress and past experiences with discriminatory police practices.

We isolated the escalation associated with the arrivals of Patrols 1 and 2 by producing a synchronised, spatio-temporal map of their approach and first contact with Nzoy. Inputs were witnesses’ videos, case-file audio and transcripts of police/witnesses hearings. Data sources were time-aligned using file metadata where available and, otherwise, via audiovisual correlation. Combining data sources, we reverse-engineered approach dynamics – estimating speed and position in time – thereby assessing the rapidity and precipitousness of the police approach. The behavioural reading is grounded in this 2D reconstruction, cross-checked against hearings and audio analysis, and interpreted alongside the Independent Commission’s psychiatric expertise and relevant literature to differentiate confusion responses from threat signals.

The third sequence focuses on Nzoy’s run and the use of the firearm by PO4. Within seconds, the situation escalated dramatically. A central point of contention is the alleged presence of a knife in Nzoy’s hands. Our detailed analysis indicates that Nzoy’s hands were open before the first two shots, contradicting police and some witnesses’ statements that he “brandished” a knife during his “attack” towards PO4. Trajectory analysis further disputes the claim that Nzoy targeted an officer for attack, instead indicating a path consistent with confusion and flight rather than aggression.

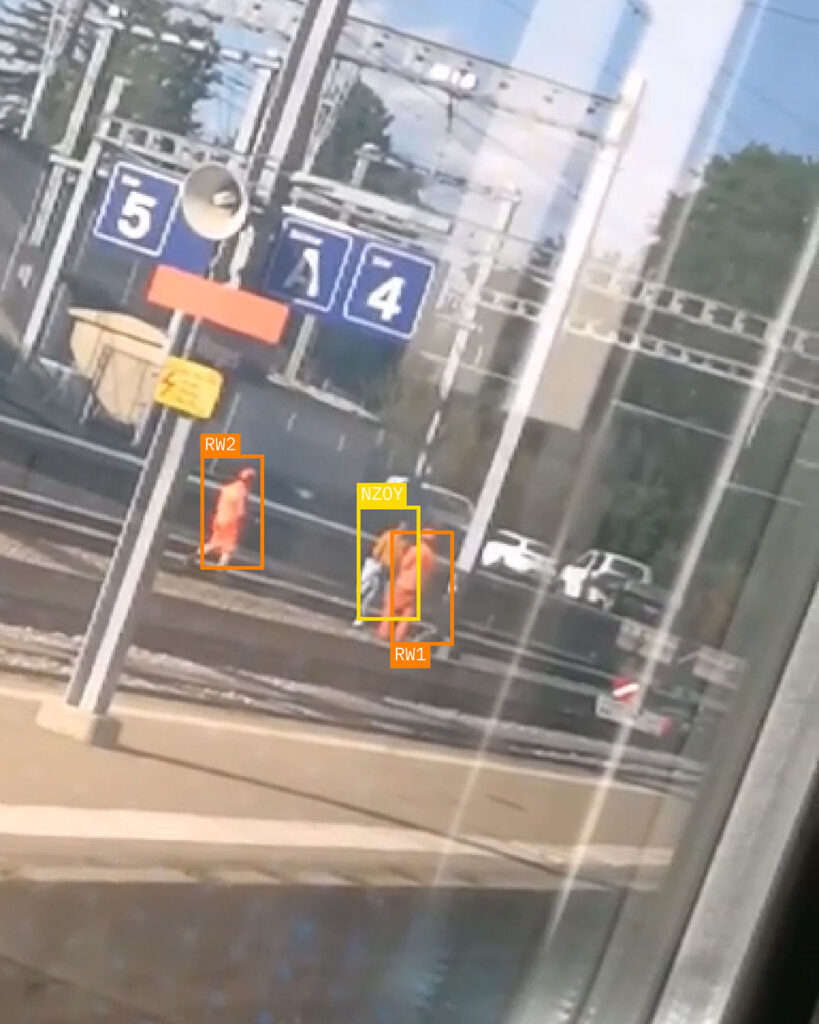

We developed a three-step demonstration: (1) hearings content analysis of “knife” references; (2) pixel-based hand analysis; (3) 2D trajectory reconstruction. First, we analysed every mention of the knife in police and witness hearings, and flagged internal/external inconsistencies, demonstrating that the sole source of hearings to assess a weapon’s presence is insufficient. Second, using the elevated witness video that shows both of Nzoy’s hands immediately before the first shots, we stabilised the clip, isolated the frames of simultaneous hand visibility, delineated hand silhouettes and measured finger–palm separations relative to forearm landmarks to classify hand state (i.e. open and empty). Third, we superimposed a perspective grid derived from platform geometry onto videos and plotted footfalls for Nzoy and PO4 frame by frame; from these tracks we were able to characterise relative motion.

The fourth and last sequence analyses the measures that were undertaken after the shots. After Nzoy was shot and clearly incapacitated, police officers prioritised coercive means, such as handcuffing him and conducting a safety search, rather than providing immediate first aid, despite visible signs of life. It was six minutes later that emergency medical assistance was provided by a nurse who witnessed the event. This delay in administering first aid highlights significant faults and a fundamental disregard for human life by the police officers involved.

We assembled a post-shooting timeline anchored at the third and last shot by synchronising multi-source videos with radio calls, then measured elapsed intervals until the nurse’s arrival to the scene (≈ 04’:40’’) and the first physical contact with Nzoy (≈ 05’:38’’), to the start of CPR (≈ 06’:00’’–06’:30’’) and the handcuff removal (≈ 07:′00″). Actions visible on video (handcuffing, body positioning, object removal, etc.) were annotated and cross-referenced with officers’ statements. We evaluated observed practices against police “Tactical First Aid” training excerpts and an independent medical assessment to determine conformity with first-aid imperatives given the absence of ongoing threat, documenting any uncertainty directly in the visual outputs.

Sequence 1: Confusion and distress

Two train fines found in Nzoy’s bag indicate that he boarded a train in Zurich bound for Geneva where he arrived at 15:47. After 28 minutes, he took a train bound for Zurich and got off in Morges at 16:41.29Case file, 8167-8168. While the announced destination on the second train fine is Zurich, the reasons he exited the train in Morges are still unclear.

The first sequence we analyse starts when Nzoy arrives in Morges at 16:41. Here, we focus on his actions as well as his interactions with two railway workers present at the scene (RW1 and RW2) to assess the situation before the arrival of the first police patrol at 17:58. By cross-referencing witnesses’ statements and video and audio data with a psychiatric assessment conducted by the Independent Commission and psychiatric literature, our analysis demonstrates that Nzoy was in a situation of confusion and distress without showing signs of aggression towards himself or people around him. Until 17:55:10, the case file does not contain any visual or audio data of this sequence. We therefore analysed witnesses’ statements to place as precisely as possible the actions of Nzoy and the two railway workers (RW1 and RW2) in time and space.

In his police hearing, RW1 states that he noticed Nzoy for the first time when he saw him kneeling and praying behind two stationed wagons near the station’s loading dock. RW1 asserts that every time someone walked past him, Nzoy would stop praying.30“Je suis arrivé à la gare de Morges à 15h36. J’ai vu un individu vers 15h37, à côté de la voie 19, derrière les deux wagons de type « fans-u », à genoux, en train de prier. J’ai continué mon travail, mais à chaque fois que quelqu’un passait près de lui, il s’arrêtait de prier.” Case file, 2003, p. 2. As the timing RW1 puts forward in his hearing is inconsistent with the arrival of Nzoy in Morges, it is impossible to precisely time how long Nzoy stayed in this part of the station.

RW1, as well as other witnesses positioned on the platform, in a train or in the building overlooking the station, further states that Nzoy crossed the train tracks repeatedly. Most of the witnesses describe Nzoy using such words as “odd”31“Je gardais un œil sur lui, саг il me paraissait farfelu […].” Case file, 2003, p.2., “lost”32“Il avait l’air un peu paumé” Case file, 2013, p.3. or “agitated”33“[…] une personne qui se trouvait sur les rails et qui semblait agité, саг il gesticulait.” Case file, 2001, p.2; “Cette personne était très agitée.” Case file, 2006, p.2. in their statements. At some point, RW1, most likely distantly accompanied by RW2, interacts with Nzoy, trying to calm him down and prevent him from crossing the tracks.

At 17:55:10, RW1 calls the police. The recording of this call constitutes the first audio data present in the case file. During this call, RW1 talks to a police dispatcher and informs them that someone is “walking around on the tracks”. In the same recording, we hear the discussion RW1 has with Nzoy in the background. He asks him to stop, to calm down and to sit down. Nzoy answers in English, telling him to “get out of here”. At some point, Nzoy speaks in French and asks the railway worker to calm down as well – “toi, calme-toi”. RW1 then asks Nzoy what he wants to do, telling him not to “act crazy”. We do not hear Nzoy’s answer and the first police patrol arrives.34RW1 : “Actuellement, on a une personne qui se promène sur les voies de la gare… […] Tranquille […] Reste cool […] Zen, assieds-toi — ” Nzoy (l’interrompant) : “ Non, mais toi, calme-toi.” RW1 : “ […] Mais dis-moi ce que tu veux faire […] Fais pas le fou…” Case file, 1001.

Although RW1 states in his hearing that he did not manage to enter into a dialogue with Nzoy as he was speaking in a language he did not know,35“J’ai essayé de dialoguer avec lui, mais il m’a répondu dans une langue que je ne connaissais pas.” Case file, 2003, p.2. the audio recording clearly shows that a dialogue was initiated. Nzoy sounds confused, does not answer – or maybe does not fully understand – RW1’s questions or words.

In his hearing, RW1 further states that Nzoy was “aggressive at times” and wanted to go towards trains, without giving more precisions.36“Il était раr moment agressif et dès qu’un train arrivait, j’avais l’impression qu’il voulait aller vers sa direction.” Case file, 2003, p. 2. In the case file, a video filmed from a train held at the station shows Nzoy surrounded by RW1 and RW2 in the area of the tracks dedicated to train manoeuvres. The video does not contain metadata but we can situate it at approximately 17:56:06. In the video, we see him trying to avoid confrontation, circling around RW1 and advancing towards Platform 4/5, with what appears to be two minor physical contacts with RW1.

In his statement, RW1 interprets Nzoy’s behaviour as “suicidal”.37“Pour moi, il avait un comportement suicidaire et je ne voulais pas qu’il passe sous се train.”, Case file, 2003, p.2. As suicidal behaviour is complex to identify and manifests in diverse ways, we refrain from putting forward any conclusion on this matter as interpreting Nzoy’s intentions at that moment is beyond the scope of this investigation.38In his police hearing, Nzoy’s father states that Nzoy mentioned suicide in the months before his death, leading to the police’s attempt to interpret the events through the lens of “suicide by cop” (2014, p. 9). No direct evidence, however, is contained in either our analysis or the case file that would substantiate a correlation between potential suicidal behaviour and his killing. Furthermore, originating in the 1980s, the concept of “suicide by cop” has since been used by police and their advocates to frame civilian deaths during interventions, effectively shifting blame and often absolving officers of accountability. Regarded by scholars as “junk science”, allowing law enforcement to rely on softer evidentiary standards and expert statements to justify excessive force, this concept is still present in police training manuals in Switzerland and elsewhere. Such use undermines civil rights and deters accountability by recasting police killings as psychological self-harm rather than potentially unjustified violence. See notably: Jeffrey Selbin, “Suicide by Cop? How Junk Science and Bad Law Undermine Accountability for Killings by Police,” California Law Review 113 (2025) With the help of the Independent Commission, we rather focus on Nzoy’s observable actions in consultation with pre-existing knowledge of his health conditions.39Case file, 7002; Case file, 7003. While large-scale studies in psychiatry consistently show that people with psychotic disorders are more likely to be victims of violence than the perpetrators,40Bertine de Vries et al., “Prevalence Rate and Risk Factors of Victimization in Adult Patients With a Psychotic Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” Schizophrenia Bulletin 45, no. 1 (2019): 114–26, https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sby020. Nzoy’s behaviour seems to indicate a state of confusion and distress, with no signs of violence or aggression towards himself or others.

During this first sequence of events, Nzoy’s actions are characteristic of someone suffering from a psychotic disorder and align with the suspicion of psychosis diagnosed in the days and in the morning preceding his death. Furthermore, Nzoy’s tendency to stay in an isolated part of the station, avoiding other people and keeping physical distance, is consistent with psychiatric research on psychosis that identifies “[n]oisy environments […] as particularly harmful […] for people with psychosis in particular” and “a well-documented source of stress”.41Sara Merlino et al., “Walking through the City Soundscape: An Audio-Visual Analysis of Sensory Experience for People with Psychosis,” Visual Communication 22, no. 1 (2023): 73, https://doi.org/10.1177/14703572211052638. In this sense, the fact that Nzoy was praying in an isolated part of the station may indicate an attempt to withdraw from the noisy soundscape of the train station, and to ground himself in a situation of distress. On this basis, it appears that at that moment, both Nzoy and the railway workers were looking for resources to deal with the situation before the arrival of the police, which led to a rapid and dramatic escalation.

Sequence 2: Police intervention and triggering effect

The second sequence we analyse covers the beginning of the police intervention, with the arrival of Patrol 1 – composed of police officer 1 (PO1) and police officer 2 (PO2) – and Patrol 2 – composed of police officer 3 (PO3) and police officer 4 (PO4). Based on an analysis of video and audio data as well as transcripts of police hearings, we assess the unfolding of this part of the police intervention and the effects it has on Nzoy. While Nzoy had been relatively calm before the arrival of police patrols, our analysis shows that the arrival and the actions of the four police officers have a triggering effect on Nzoy, leading to a rapid escalation of the situation.

At 17:55:37, the police dispatcher, who is on the phone with RW1, specifically calls upon Patrol 1 who are stationed in front of Morges station in a police patrol car.42“[…] est-ce que tu pourrais, s’il te plaît, te rendre en gare ? On a un gars qui est sur les voies. [La patrouille 1 demande à répéter] On a un gars sur les voies. Si tu pouvais juste aller regarder, s’il te plaît, j’ai l’informateur en ligne”, Case file, 1001.

After confirming their intervention on the radio, a surveillance camera captures PO1 and PO2 running inside the station from the station’s main entrance.

At 17:56:27, while Patrol 1 is entering the station, we hear in the same radio recording a communication initiated from the car of Patrol 2. PO4, part of Patrol 2, informs the police dispatcher that they are close to the station and intervening. The sirens of the police car that can only be activated in an emergency can be heard in the background:

Assessing the necessity and urgency of Patrol 2’s intervention

The intervention of the two police patrols is depicted in a simplified manner in the police investigation report, which states that “two police patrols were dispatched to the scene”.43“Deux patrouilles étaient dépêchées sur les lieux et arrivaient vers 17:58” Case file, 4001, p.48. As Patrol 2 includes PO4 – the police officer who shot Nzoy – and since only Patrol 1 was specifically called upon to intervene at Morges station by the police dispatcher, the reasons why Patrol 2 intervened as well – and with this degree of urgency – need a careful examination.

In their hearings on the night of the event, PO3 and PO4 both claim that it was due to their proximity to the events that they decided to intervene.44“[…] nous nous rendions aussi sur place, spontanément, саг nous étions а proximité de la gare” Case file, 2002, p.4; “À ce moment-là, au vu de notre proximité de l’intervention, mon collègue a enclenché les moyens prioritaires, soit les feux et les klaxons.” Case file, 2007, p.4. In a second hearing, PO3 further states that they “decided to intervene urgently because it is a risk context, given that it is a train station”.45“[…] nous avons surtout décidé d’intervenir en urgence, car il s’agissait d’un contexte à risque, s’agissant d’une gare.” Case file, 2021, p.3. While PO3 mentions that they heard another patrol was engaged and that they decided to intervene spontaneously,46“[…] nous nous rendions aussi sur place, spontanément, саг nous étions à proximité de la gare” Case file, 2002, p.4. PO4 states that there was “too much noise” on the radio traffic and that “a patrol was maybe closer than [them]”.47“Malheureusement pour nous, il y avait trop de bruit sur les ondes pour cette intervention. Il y avait une patrouille qui était peut-être plus proche que nous : il s’agissait de la [Patrouille 2].” Case file, 2007, p.4.